by Tanya Southcott on behalf of McGill’s 2014 Ambassadors: Heather Braiden, Susane Havelka and myself

This past May, the Vernacular Architecture Forum welcomed me and two other graduate students from the School of Architecture at McGill University to the annual conference in Down Jersey as part of the Ambassadors Award program. The three of us had attended our first VAF conference together the previous year, when the Forum travelled north of the border to picturesque Gaspé-Percé, Quebec. In the spirit of this transnational exchange, I would like to share a more personal connection from our visit this year, a moment of coincidence between the histories of Margate, a seaside resort on the southerly end of Atlantic City, and St. Thomas, Ontario, a former railway capital in the southwest of the province, and, incidentally, the city where I grew up.

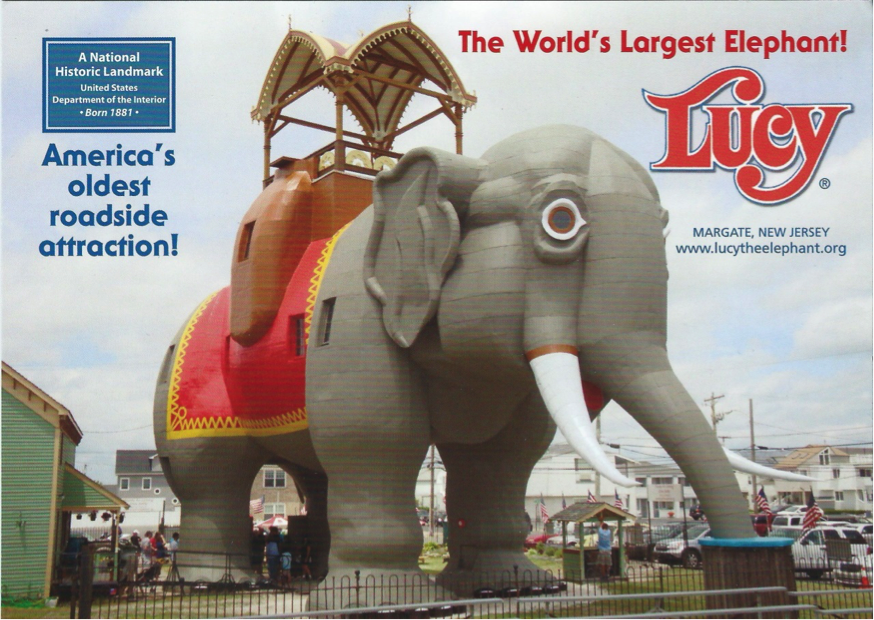

A footnote to the exhibition housed in the giant timber-framed belly of Margate’s famous elephant Lucy names Jumbo (1861-1885), of Barnum & Bailey’s fame, as James Vincent de Paul Lafferty Jr.’s muse in the creation of his patented elephant building. Showcased as “the biggest elephant or mastodon – or whatever he is – in or out of captivity” by legendary showman Phineas Taylor (P.T.) Barnum, Jumbo was arguably the most famous animal in the world during his short lifetime. Born in the French Sudan (now Mali), he was traded to a wild animal collector in Zanzibar and eventually consigned to the Jardins Des Plantes in Paris. Four years later, in exchange for a rhinoceros, he was traded to the Royal Zoological Society of London where he was christened Jumbo, from the Swahili jumbe meaning chief, and celebrated as “the first African elephant to reach England alive”. Jumbo attracted Barnum’s attention while at the London Zoo where he was purchased for $10,000 and shipped onboard the Assyrian Monarch to his new home in New York.

A footnote to the exhibition housed in the giant timber-framed belly of Margate’s famous elephant Lucy names Jumbo (1861-1885), of Barnum & Bailey’s fame, as James Vincent de Paul Lafferty Jr.’s muse in the creation of his patented elephant building. Showcased as “the biggest elephant or mastodon – or whatever he is – in or out of captivity” by legendary showman Phineas Taylor (P.T.) Barnum, Jumbo was arguably the most famous animal in the world during his short lifetime. Born in the French Sudan (now Mali), he was traded to a wild animal collector in Zanzibar and eventually consigned to the Jardins Des Plantes in Paris. Four years later, in exchange for a rhinoceros, he was traded to the Royal Zoological Society of London where he was christened Jumbo, from the Swahili jumbe meaning chief, and celebrated as “the first African elephant to reach England alive”. Jumbo attracted Barnum’s attention while at the London Zoo where he was purchased for $10,000 and shipped onboard the Assyrian Monarch to his new home in New York.

Perhaps Lafferty saw the great elephant here, exhibited by Barnum at Madison Square Garden, or somewhere along the railway lines that carried the travelling circus with Jumbo as its star attraction across both state and national borders. The spectacle attracted no shortage of media attention, as Barnum was notorious for sensationalism and the shameless promotion of his enterprise. He was most interested in things gigantic and the first of their kind, and the elephant’s value was directly proportional to the size of his body. Inevitably, Jumbo proved an asset either living or dead.

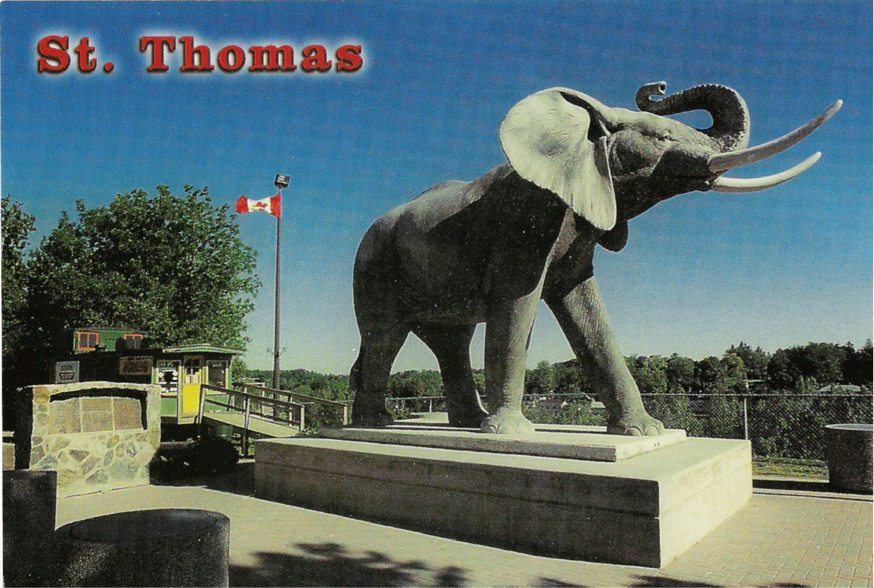

On September 15th, 1885, Barnum’s circus was travelling through St. Thomas, Ontario, a significant railway junction and newly incorporated city. Following the evening’s performance, as the elephants were loading onto their respective railway cars, an unscheduled train travelling along the Grand Trunk Line took the animals and their keeper by surprise. Jumbo was struck by the oncoming train with a force that propelled him down a steep embankment where he died shortly after. Barnum promptly had the hide stuffed and mounted by Professor Henry Ward of Ward’s Natural Science Institute in Rochester as the new showpiece of the circus’s travelling exhibit. Jumbo’s heart was sent to Cornell University in Ithaca and his skeleton to the American Museum of Natural History in New York. After a season of touring, his skin was sent to Tufts College in Medford, Massachusetts, where it was destroyed by fire in 1975.

I grew up in the shadow of Jumbo the Elephant, or rather his life-sized replica. In 1985, in honor of the centenary of the elephant’s death, and in appreciation for a hundred years of world fame, the City of St. Thomas commissioned a statue of the elephant by east-coast artist Winston Bronnum, one of Canada’s leading animal sculptors. Constructed of concrete and reinforced with steel, the statue was poured in two sections to aid its transportation 1,070 miles across the Trans-Canada Highway from Sussex, New Brunswick. The lower part of the legs and six inch base were joined to the upper part of the legs and body by four large concrete pegs on site. Once assembled, the piece weighed thirty-eight tons, the body hollow with 7 inch thick walls, layered with an extra three-quarter inch of textured cement and sand plaster to emulate elephantine skin. The official unveiling of the monument marked the highlight of Jumbo Days, a five-day civic celebration, during which time over 10,000 people were drawn to the site to pay tribute to the elephant. Today Jumbo overlooks the city’s main thoroughfare, adjacent to the Elgin County Pioneer Museum on a site not far from the circus’ original pitching grounds.

I grew up in the shadow of Jumbo the Elephant, or rather his life-sized replica. In 1985, in honor of the centenary of the elephant’s death, and in appreciation for a hundred years of world fame, the City of St. Thomas commissioned a statue of the elephant by east-coast artist Winston Bronnum, one of Canada’s leading animal sculptors. Constructed of concrete and reinforced with steel, the statue was poured in two sections to aid its transportation 1,070 miles across the Trans-Canada Highway from Sussex, New Brunswick. The lower part of the legs and six inch base were joined to the upper part of the legs and body by four large concrete pegs on site. Once assembled, the piece weighed thirty-eight tons, the body hollow with 7 inch thick walls, layered with an extra three-quarter inch of textured cement and sand plaster to emulate elephantine skin. The official unveiling of the monument marked the highlight of Jumbo Days, a five-day civic celebration, during which time over 10,000 people were drawn to the site to pay tribute to the elephant. Today Jumbo overlooks the city’s main thoroughfare, adjacent to the Elgin County Pioneer Museum on a site not far from the circus’ original pitching grounds.

Jumbo’s Statistics:

- Largest diameter of the ear: 5 feet 5 inches

- Circumference of tusk at the base: 1 foot 6 inches

- Circumference of trunk at base: 3 feet 5 inches

- Length of trunk from base of tusk: 5 feet 11 inches

- Body circumference, just back of shoulders: 16 feet 4 inches

- Body circumference at middle: 18 feet

- Length of tail: 4 feet 6 inches

- Circumference of foot at foreleg: 5 feet 3 inches

- Circumference of leg (3 feet above sole of foot): 3 feet

- Circumference of leg (4 feet above sole of foot): 4 feet 8 inches

- Height measuring from sole of foot to a point between shoulder-blades: about 12 feet

- Entire length of animal: 14 feet

- Weight of heart: 46 pounds

- Weight in life: 7 tons

- Weight of mounted skeleton: 3 tons