- Home

- Awards & Fellowships

- Glassie Award

- Past Glassie Winners

Glassie Award Winners

2025 Bernard L. Herman

Remarks given by Jeff Klee at the 2025 Delaware Conference

This year, I am proud to report that the VAF gives the Glassie Award to Bernard L. Herman (1951-2024).

A conventional retrospective would have recited his professional accomplishments, including his ludicrous record of publications across a huge range of academic fields, and his service to the VAF, which included organizing the first Delaware conference 41 years ago. Bernie was there at the beginning, when the proto-VAF was known as the Friends of Friendless Farm Buildings. And he was very much there as the VAF found its footing as a venue for serious conversations about the built environment, editing two of the first five volumes of Perspectives in Vernacular Architecture, writing the most useful instruction manual for fieldwork, and publishing three additional books on early American architecture, all of them winning the Cummings Award. Most of us would give our left kidney to achieve that much in a lifetime and he did it all by the time he was 54 years old.

But it was just a first act. His second act started in 2009, after he became chair of Southern Studies at the University of North Carolina, where he indulged his long-standing interests in outsider art and southern food. As his research turned toward the creativity of the living, he was a less conspicuous presence at VAF conferences and his absence has made those meetings a little less lively and a little less amusing.

A conventional resume of Bernie’s career would continue to celebrate how he mentored a generation of students who have grown up to lead this organization, including Louis Nelson, Susan Garfinkel, Anna Andrzejewski, Gabrielle Lanier, Cindy Falk, Jeroen van den Hurk, Sherri Marsh, and 55 others from various programs at Delaware. Reciting all of this would discharge my basic obligation as an awards presenter but would fall far short of articulating what was singular, and significant, about Bernie Herman. Because the most distinctive and exceptional part of Bernie was not his intelligence or his work ethic but his essential humanity—his sense of humor, his faith in the decency of people, and his disdain for easy answers to simplistic questions. He inspired generations of scholars to look harder to identify the poetry that was all around them.

Poetry, or “Poetics,” was a favorite image of Bernie’s. Sometimes he used this in the conventional way, referring to the rhythmic and metaphoric arrangement of words. But Bernie recognized poetry everywhere: in the built environment; in the snap of a well-told joke; in the careful seasoning of a stew; and in the little assemblages he started creating for his wife, Becky, late in life. Identifying the poetics of the everyday took effort and a keen eye. It’s easy enough to recognize the poetics in Borromini’s chapels; it takes real skill to find it in the barns of Lancaster County. It takes creativity, too, and a certain sensibility; an openness to the strange and the awkward and a desire to celebrate the overlooked and under-appreciated. This attitude is surely why he had such an affinity for graduate students.

A point that is lost in emphasizing Bernie’s brilliance and productivity is that his academic career was just one part of his life. It wasn’t that community engagement and student advising were in service to his career; if anything, it was the other way around. Scholarship in the conventional sense of peer-reviewed publications wasn’t the center of his life, it was just one part of his larger, enormous self.

Bernie was an exceptionally productive author but it was important to him to do work whose worth wasn’t measured in the quantity of citations. He devoted much of his time to sustaining the culinary traditions of the Eastern Shore of Virginia, cultivating an orchard of heirloom figs and personally re-seeding some of the oyster beds of the Chesapeake Bay. When a working-class neighborhood of Newark, Delaware was threatened with demolition, Bernie wrote a book documenting its history and culture; he followed this with another, celebrating the neighborhood’s home cooks and preserving their recipes.

As this example illustrates, Bernie was generous. Generous with his expertise, his knowledge, and his skills, certainly, but also with his things. At his retirement, he gave me the staggering gift of his architectural library, 37 boxes of books. Other gifts were more ephemeral, but their rewards just as durable: to me, one was a week spent with Bernie surveying small houses on the North Shore of Boston, a formative experience. To a young Louis Nelson, he gave the update of National Register Nominations for 18th century houses in Delaware. And to Gabrielle Lanier, he gave co-authorship of a book on fieldwork. In all of these projects, he threw his students into the deep end of the methodological pool so that we could discover for ourselves that we had the skills we needed to stay afloat in this field.

Bernie relished recruiting and advising graduate students, whether they were interested in Baroque prints or American genre paintings or Zuni pueblo. To him, what counted was not the subject matter but the quality of the questions that we were asking. He did not set out to become an expert in early American architecture; he set out to indulge his curiosity and to stimulate curiosity in others. Nonetheless, some regarded him a little warily, supposing that he was just another middle-aged leftist in Doc Martins. And quite a few found his casual use of the language of critical theory off-putting. But that, too, was an expression of esteem: the message here was, “you are intelligent; I respect you as a peer,” even if the result was the student hustling off to consult the Encyclopedia of Semiotics. A few students took to referring to him as Bernie Hermeneutics. His linguistic performances on the page, in the classroom, and in the hallway were above all an invitation—an invitation to a conversation about objects, politics, and the social world.

His most valuable advice to students didn’t concern getting through the foundational literature, developing a method, writing a successful fellowship application, or any of the other basics. He knew that we’d figure that out on our own and he would re-direct us if he spotted us wandering too far into the desert. He urged us to read fiction, and poetry, and archaeology. He especially liked Charles Olson’s Maximus poems, a recommendation that too few of us took up.

But this was another invitation; an invitation to an expanded view of the world, to other possibilities besides the comfortable, collegiate outlook that had us all striving for some version of the same thing: good recommendations from our teachers and a solid GPA, with peer-reviewed publications and a tenure-track appointment on the horizon. Bernie’s invitation, both to his students and to his peers, was to have a little courage; to broaden our outlook; to find kinship with people where it wasn’t expected; to open ourselves up to others.

His invitation, in short, was to a life whose goals were understanding and empathy not personal comfort and professional standing. But it was also to a life filled with manifold pleasures: intense art and fresh oysters and heirloom figs and outrageous stories and complex poetry and friendless farm buildings. My scholarship is better; and my life is better because I accepted that invitation.

So thank you, Bernie, for all of it.

2019 Richard Longstreth

Remarks given by Ken Breisch at the 2019 Philadelphia Conference

As many of you know, the Henry Glassie Award was first presented by VAF in 1999 and is named for this renowned scholar of vernacular architecture and folklore. It recognizes special achievements in and contributions to the field of vernacular architecture studies, and is only awarded intermittently, as deemed appropriate by the VAF Board of Directors.

It is my great pleasure and honor tonight to announce that the winner of the 2019 Glassie Award is Professor of American Civilization, Emeritus, at the George Washington University, Dr. Richard Longstreth.

Since receiving his PhD at the University of California at Berkeley in 1977, early on at Kansas State University, and particularly as professor of American Studies and director of the Graduate Program in Historic Preservation at the George Washington University, Dr. Longstreth has secured his reputation as a great scholar, teacher, mentor and preservationist. Over the years, he has trained dozens of students who have gone on to become highly respected preservation professionals and scholars. Along with their mentor, they (and many of you are here this evening) have helped reshape the fields of architectural history and heritage conservation on multiple levels.

This was most evident to those of us who were fortunate enough to attend the symposium held in his honor earlier this week. His influence has extended far beyond that of his immediate students to the work of many of the most important scholars in our field.

Dr. Longstreth is himself one of the most highly respected of scholars in architectural history studies. In this realm, the term prolific is not nearly adequate enough to describe his work. He has published or edited more than fifteen books on a wide range of American architectural forms and types, including California regionalism at the turn of the last century, the Mall in Washington. D.C., and urban commercial and roadside vernacular buildings. His book, City Center to Regional Mall: Architecture, the Automobile, and Retailing in Los Angeles, 1920-1950, was recognized with no less than four awards by national academic organizations in the fields of historic preservation, and architectural and urban history. These honors included the 1998 Abbott Lowell Cummings Prize, which is bestowed by this organization annually to the publication that has made the most significant contribution to the study of vernacular architecture and cultural landscapes during the previous two years.

And I can personally attest that this book alone has reshaped that way that we way out on the West Coast have come to understand and view our city.

This masterful study of commercial development in Los Angeles and the impact of the automobile on the urban landscape, forms a companion of sorts to two other books by Dr. Longstreth, The Drive-In, the Supermarket, and the Transformation of Commercial Space in Los Angeles, 1914-1941, published in 1999 and more recently, The American Department Store Transformed, 1920-1960.

In addition to writing and editing books, Richard has contributed to an astonishing array of other publications, including, but not limited to, the APT Bulletin, Architectural Record, The Harvard Architecture Review, the Historic Preservation Forum, Perspecta, Winterthur Portfolio, the Journals of the American Planning Association, the Society of Architectural Historians, and Urban History, as well as Buildings & Landscapes.

In addition to writing and editing books, Richard has contributed to an astonishing array of other publications, including, but not limited to, the APT Bulletin, Architectural Record, The Harvard Architecture Review, the Historic Preservation Forum, Perspecta, Winterthur Portfolio, the Journals of the American Planning Association, the Society of Architectural Historians, and Urban History, as well as Buildings & Landscapes.

In 2010 Dr. Longstreth, his students and alumni organized and hosted the annual conference of VAF in Washington, D.C. The guide for this meeting appeared as Housing Washington: Two Centuries of Residential Development and Planning in the National Capital Area, a volume also edited by Richard.

Over the years Professor Longstreth has also served on the boards of, and as an officer of numerous organizations. From 1989 to 1991, as first vice president of the Vernacular Architecture Forum; 1998 to 2000, as president of the Society of Architectural Historians, and president of the Frank Lloyd Wright Building Conservancy from 2013 to 2015). He was a trustee of the National Building Museum from 1988 to 1994, and a board member of Preservation Action, 1980 to 1995; the Historical Society of Washington, D.C., 1994 to 1998; and a member of the National Historic Landmarks Advisory Group from 1989 to 1994, He has also served on and chaired the Maryland Governor's Consulting Committee on the National Register of Historic Places.

Dr. Longstreth is himself one of the most highly respected of these scholars in vernacular studies—but also it the field of historic preservation. He has figured prominently in efforts to save significant historic properties of nearly every ilk, especially those dating to the mid and late twentieth-century. He has written extensively on the significance of these historic resources, as well as other often misunderstood and under-appreciated buildings and places, especially in the realm of vernacular building. Several of his articles in this arena have become classics in the field and decades later continue to be cited frequently, and they have in numerous cases contributed to the reshaping of federal preservation policies—or the way they are interpreted and implemented. The most important of these essays were collected in his book, Looking Beyond the Icon, which was published in 2015.

Although some of you may not know Richard—probably not many—, you will probably recognize him as the big guy with the big camera bag seated in either the first or second row of our tour buses, so that he can be among the first off to set up his tripod and photograph whatever site we may be visiting. Many of you will also recall that this prime location on the bus—no matter where it seemed we were travelling, whether the backroads of New Mexico or somewhere in Utah, Kansas, Wisconsin—or the other day in Philadelphia--allowed him to “borrow” the microphone from our tour guide in order to inform us of some obscure little gem we were about to see around the next curve in the road.—because he had already been there some years before!! Or to add some obscure antic dote about the place we were passing. If not that, you probably have heard his booming voice, at some reception or other, ordering us to be quiet so that some announcement could be heard, or speaker introduced.

I have been honored and—amused--to know Richard for more than three decades and--given his immense contributions to our understanding of the American landscape in its many and varied forms, I cannot express how deeply he deserves this award this evening.

2018 Alison K. (Kim) Hoagland

Remarks given by Sarah Fayen Scarlett at the 2018 Potomac Conference

Remarks given by Sarah Fayen Scarlett at the 2018 Potomac Conference

I’m incredibly honored to have been asked here tonight to help present the 2018 Glassie Award to Alison K. Hoagland, better known to all of us as Kim.

Kim has long been a champion of American buildings -- often some of the humblest and hardest to get to -- and she has also been a champion of vernacular architecture scholarship, through her own active publication and editing, her teaching and mentorship, and her long dedication to the VAF. She served as President of this organization in 2008-09, and before that as First Vice President, elected board member, Papers Selection chair and committee member, as editor of the Special Series published by University of Tennessee Press, and now as Second Vice President in charge of conferences.

As all of us at the VAF are well-attuned to geography, I think we can all appreciate how fitting it is to recognize Kim here on the banks of the Potomac, since Washington, DC has been one of Kim’s home bases over many years. After majoring in American Civilization at Brown University, Kim moved here to DC to attend George Washington University, where she received a master’s in American Studies with a concentration in Historic Preservation in 1979. She went right to work for HABS, where she served as historian and then senior historian until 1994.

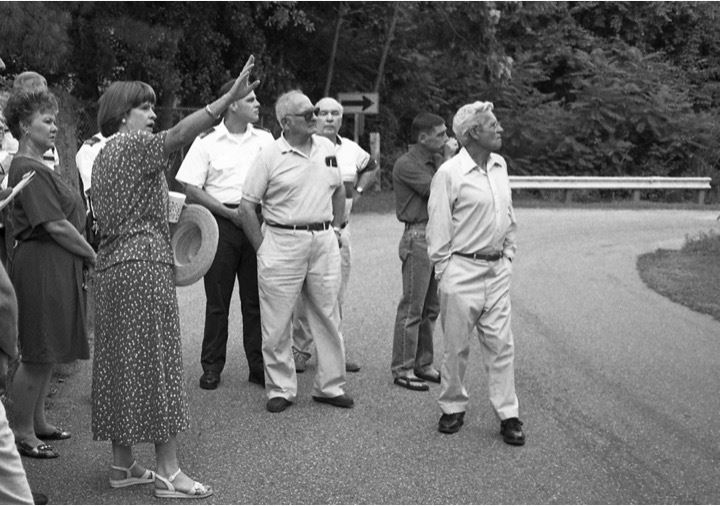

In those years, Kim made meaningful contributions to the content and methods of field work at HABS. There, her intrepid spirit and dedication to often neglected cultural resources took her to out-of-the-way-places including being part of the 1984 HABS summer field crew in Gates of the Arctic National Park, which you see here. This and other work in Alaska resulted in Kim’s 1993 book Buildings of Alaska, among the first in the Buildings of the United States series published by the Society of Architectural Historians. Among her lasting contributions to practice at HABS are the guidelines for field documentation that are still followed by field crews of staff and students today.

Now if you draw a line between DC and Alaska you will just about pass by the south shore of Lake Superior -- which became another major home base for Kim, when she took a faculty position at Michigan Technological University in their Industrial Heritage and Archaeology program in 1994. The person who hired her, our colleague Larry Lankton, told me that he’d been trying to hire Kim ever since 1979 when she was the best student in his class at GW -- but she got a better offer from HABS. He’d been trying to steal her away that whole time -- mostly because he knew Kim was the right person to study the company housing and paternalistic landscapes that defined Michigan’s Copper Country, a mining region that boomed in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. And indeed she was. Over the next 15 years, Kim documented hundreds of buildings and wove them into a richly interpreted narrative that appeared in 2007 as Mine Towns, University of Minnesota press.

another major home base for Kim, when she took a faculty position at Michigan Technological University in their Industrial Heritage and Archaeology program in 1994. The person who hired her, our colleague Larry Lankton, told me that he’d been trying to hire Kim ever since 1979 when she was the best student in his class at GW -- but she got a better offer from HABS. He’d been trying to steal her away that whole time -- mostly because he knew Kim was the right person to study the company housing and paternalistic landscapes that defined Michigan’s Copper Country, a mining region that boomed in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. And indeed she was. Over the next 15 years, Kim documented hundreds of buildings and wove them into a richly interpreted narrative that appeared in 2007 as Mine Towns, University of Minnesota press.

While in the Upper Peninsula, Kim took on the role of teacher and colleague to a new and growing community. She taught the art and science of documenting historic structures to a generation of graduate students, many of whom credit Kim’s class as the basis of their own documentation practices today as scholars and cultural resources managers. She brought experiential learning to her undergraduate students before that was even a thing -- I have heard about a final exam in her History of American Architecture class in which she gave each student a street address and a blank piece of paper and sent them out to write her an interpretation of the building on the spot. It was Kim’s vision that has made the study of the built environment a vital part of our curriculum at Michigan Tech, and I am thankful for that every day, as the inheritor of her faculty position (and also her office and a number of her wall posters). Outside the university, our community has also benefitted from Kim’s dedication to public history. She has written interpretive walking tours, given countless public lectures and architectural tours, written or advised numerous nominations to the National Register, and served as the head of the Keweenaw National Historical Park Advisory Commission, which gives grants for heritage and preservation throughout the region.

Even on top of all of these contributions, perhaps Kim’s most influential role that we celebrate tonight has been in the area of publications. She has been consistently writing and editing meaningful articles and books over her whole career, which taken as a whole have helped establish and drive forward vernacular architecture as an area of scholarship. She has co-edited two editions of Perspectives in Vernacular Architecture, contributed three articles there and to Buildings & Landscapes, as well as to many other journals, edited volumes, and encyclopedias. And she published Army Architecture in the West in 2004. In fact, it was her prolific research and writing drive that ultimately led her to retire early from Michigan Tech because, in her own words, “I have too many books I want to write!” And indeed that’s what she is doing now. Splitting her time between a condo in Capitol Hill and a fabulous 1930s kit-built cabin on the banks of Lake Superior, Kim is continuing to help us decipher the material and cultural meanings of our built environment. Her book The Log Cabin has just come out from the University of Virginia Press; the publication of her book about Bathrooms is imminent; and a new project about building policies for DC rowhouses in underway. In fact, a colleague staying with Kim a few weeks ago was astounded to realize that in one day Kim was taking calls about and writing text for THREE BOOK PROJECTS at the same time! While Kim makes research and writing and publishing look easy, we are recognizing tonight the model that Kim has set for all of us when she creates such rich interpretive context around the keenly observed details of structures and building practices to better understand the lived experience of workers, builders, soldiers, women, and so many others.

As a final note -- just Thursday on our tour of the Western Shore Kim and I both ended up waiting in line for the bathroom at St Francis Xavier Catholic Church. And Kim took it upon herself to go to battle with a dysfunctional paper towel dispenser. And while she was ultimately unsuccessful in fixing this contraption, I actually heard someone say, “Kim, you should get some kind of award for this!” So Kim — for all of your contributions — big AND small — that have furthered the study of vernacular architecture, we present you with the Glassie Award.

2017 Carl Lounsbury

Remarks given by Jeff Klee at the 2017 Salt Lake City conference

Remarks given by Jeff Klee at the 2017 Salt Lake City conference

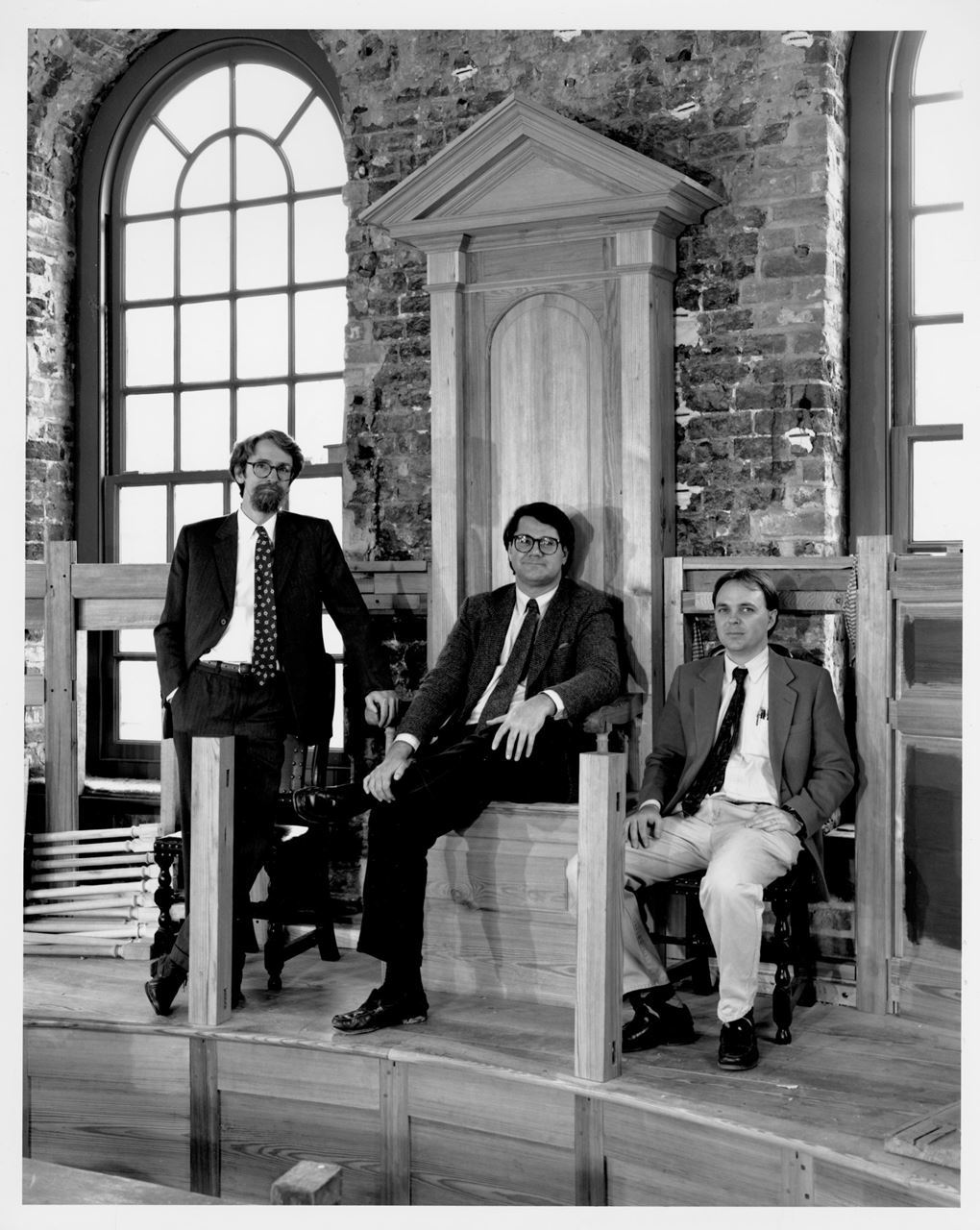

Two years ago, we honored Catherine Bishir, one of only two people in the world who have attended every single meeting of the VAF since it founding. This year, I'm pleased to say, we celebrate the other: Carl Lounsbury.

Now despite what you might think, the man known in high school as golden toe Lounsbury for his skills as a place kicker is not known around Virginia as Mr. Excitement. He's been using the same brand of soap for his entire adult life. It was seen as uncharacteristally flamboyant for him to buy a gray Camry, breaking a 25-year run of beige. And yet his has been a life filled with adventure. One of the many things that he shares with James Bond is that there have been attempts made on his life in both Venice and Jamaica. But today we honor Carl not for a life of derring-do, but for his work as a scholar and a major contributor to the success and the remarkable culture of the VAF.

Carl has been with the VAF from the beginning, from the days when the newsletter circulated in mimeographed typescript, the paper sessions came at the end of a long day of touring, eating, and drinking, and when a conference could be thrown together in about a month. In 1980, when this group was founded, Carl was just a promising young graduate student, somehow working simultaneously towards degrees in American studies at George Washington University and in architecture at NC State. A native of Winston-Salem, he came back to Carolina to conduct surveys in Alamance county and Southport. Those of you that went on the Stagville tour at last year’s conference enjoyed some of the fruits of his earliest research, including his oral histories with former residents. It was then, too, that he started working with Catherine Bishir on Architects and Builders in North Carolina, the first of Carl's books to win the Cummings award.

But a promising career in North Carolina was interrupted in 1982, when he was hired by the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, where he joined Cary Carson, Ed Chappell, Willie Graham, and Mark Wenger. Among this already accomplished, ambitious group, Carl quickly established himself as both a careful fieldworker and a determined researcher, canvassing Virginia’s courthouses and libraries to compile an exhaustive documentary archive. This work would form the basis of his subsequent work on public buildings and of course, the indispensable Glossary of Early Southern Architecture and Landscape, which, by the way, was the second of Carl's books to win the Cummings award.

This early work in municipal records was joined by a longstanding program of fieldwork on public buildings and churches, research that led to the publication of his book on courthouses in 2005. For those keeping score, that was Cummings award #3. The church book is in progress but it's safe to say that it will be his magnum opus, the most comprehensive view of early American church architecture yet written.

Carl has been the most prolific member of the Williamsburg staff but he has not achieved that status by going it alone. The Chesapeake House, edited by Carl and Cary Carson but written by many collaborators, is exhibit A. As a group project, it proceeded more slowly than Carl might have liked, but the quality of the result testifies to the benefits of patience, determination, and genuine scholarly cooperation. Many academic departments like to congratulate themselves for their collegiality, which usually seems to mean that the faculty tolerate one another. The Williamsburg office was collaborative. The work was shared, both in the field and around the drafting table. This isn't collegiality. It's friendship.

Carl has friends far beyond the little circle in Williamsburg, thanks to his generosity with his expertise, but also thanks to his decency, his excellent sense of humor, and his treatment of students and inexperienced junior colleagues as peers. These qualities have made him a mentor to many. Through his classes at William and Mary, the University of Virginia, and Virginia Commonwealth University, he has taught hundreds of students, including a young Louis Nelson, who became an unofficial fifth member of the department of architectural research in Williamsburg for a little while in the 1990s. Carl has also been generous with his fellow scholars, both in the states and in the UK. He has organized conferences, including the 2002 VAF meeting, symposia, and memorable field tours. One very lucky group got to follow him around England for three weeks looking at parish churches.

One of the reasons that Carl has drawn so many of us into his friendly orbit is that, although he takes his work, and this organization, very seriously, he doesn't take himself that seriously. Like Abbott Cummings, who we remember fondly today, he wears his status as a guru very lightly. Maybe his humility is a product of his Moravian upbringing. Or maybe it comes from being a careful student of Cary Carson, his graduate and professional mentor. Either way, Carl is not someone who seeks accolades and recognition, which makes giving this award to him all the more enjoyable.

Carl, for your large body of rigorous, historically grounded scholarship, for your selfless dedication to the VAF, for your generous, good-humored mentorship of so many, and finally, for making the people around you better by your example and your support, this year’s Glassie award is for you.

Edited remarks by John Larson, Old Salem, on the presentation of the Henry Glassie Award to Catherine Bishir, 4 June 2016

It is fitting that tonight, in Durham, we present this award to the voice of North Carolina architecture, Catherine W. Bishir. Although a native of Kentucky, after studying English at the University of Kentucky and then at Duke University, North Carolina became Catherine’s beloved Old North State, her “valley of humility between two mountains of conceit.” The architecture, landscapes and people quickly merged with her down home personality, temperament and intellectual inquisitiveness. By 1971 she was employed by the North Carolina Division of Archives and History where she spent the better part of the next thirty years. In 1973, she became Head of the Survey and Planning Branch and it is from that bully pulpit that she profoundly altered traditional perceptions of North Carolina architecture. She recruited a cadre of architectural historians and, although the frugal State of North Carolina would pay no benefits, the opportunity to work with Catherine was benefit enough. She brought a new way of looking at traditional buildings (initially called the “Bishir Braille” method, because staff swore that she could identify any North Carolina building with her eyes closed!). She was a quick study, a voracious reader and an exacting editor, eager to listen and ever willing to share. Openness and high energy define years of her coordinated survey work in North Carolina.

Catherine builds partnerships. Her relationship with the North Carolina State University began in 1978 with the publication of Carolina Dwellings, where Catherine’s article “A Study of High-Style Vernacular Architecture in the Roanoke Valley” added the term “vernacular” to the North Carolina architectural lexicon. She has now come full circle, returning to NC State as Curator in Architectural Special Collections and creating an expansive digital biographical library of North Carolina Architects and Builders.

In 1980, Catherine was encouraged by Carl Lounsbury to become a founding member of Board of Directors of the VAF – and she has never missed a conference, tonight surpassing the thirty-seven year mark. No one has held more VAF offices, served on more committees, been on more tours, edited more articles, or encouraged more members than Catherine W. Bishir. She is the Ms. Never Met a Stranger; Aren’t We Having Fun? and Rotate Your Seat on the Tour Bus! queen of the VAF. This tsunami of enthusiasm rained down on me, as a newly appointed Director of Restoration at Old Salem, when we hosted the third annual meeting of the VAF in 1982. I can personally testify that Catherine has changed my life—as she has for so many of us here tonight.

Her colleagues say that Catherine Bishir has a natural head for architecture, and that is surely true, but it is also her literary skill that will leave a lasting mark not only in North Carolina but in the field of vernacular architectural studies as a whole. She often publicly exhibits her love of letters and it is an enthusiasm that she has sought to instill in so many of us over the years. This talent has allowed her to write in a scholarly style that is crisp and accessible to a wide audience.

In 1990, Catherine co-authored Architects and Builders in North Carolina and published North Carolina Architecture, clearly establishing herself as the state’s leading architectural historian. Catherine immediately took on celebrity status which she accepted with the typical grace and humility that has defined her over the years as she lectured widely, authored and co-authored many books and articles, and won many awards, including the Order of the Long Leaf Pine by the Governor of North Carolina, an honorary membership in the AIA, and the Robert Stipe Award as a leading North Carolina preservationist. Her intellectual reach seems unlimited—what a fertile mind that can move so freely from Women, Politics, and Confederate Memorial Associations to Yuppies, Bubbas and the Politics of Culture!

Catherine has reflected, “It has been an extraordinary privilege to travel the state and meet its history, its buildings and its landscape and the people who love them.” It has been our privilege to travel with her. And so, our dearest colleague, our friend, our very own Queen of Bubba, our champion of all things vernacular and of the VAF that gathers here tonight, with heartfelt gratitude and affection, we present the 2016 Henry Glassie Award to you, Catherine W. Bishir.

It is difficult to imagine a person who has achieved more or contributed more to the field of vernacular architecture studies than the recipient of this year’s Henry Glassie Award, Dell Upton. Upton is a graduate of the storied Brown University program in American Civilization, where his dissertation committee included chair James Deetz, and readers George Monteiro and Henry Glassie. He began his professional career as an architectural historian with the Virginia Historic Landmarks Commission in the mid-1970s.

As one of the founders of the Vernacular Architectural Forum in 1979, he served as the first editor of our newsletter, Vernacular Architecture News. In those pre-internet days, those mimeographed, later printed newsletters, and Dell as its editor for ten years served as the indispensible clearinghouse for information on the quickening of scholarship on everyday buildings and landscapes. VAN and Upton’s own growing stature gave the VAF intellectual credibility, and helped create our community of scholars.

Upton’s own voracious reading and centrality to this emerging discourse, positioned him to edit two influential 1986 collections. Common Places, edited with John Vlach, sampled a rich range of topics, research methods and interpretive strategies, and demonstrated the depth and vitality of the field. America's Architectural Roots broke out of the early east coast focus of the field, even more definitively, to suggest an inclusive range of ethnic and regional traditions.

Remarkably that same year, 1986—while still the editor of VAN—Upton also published his first great scholarly monograph, Holy Things and Profane. The book is so inventive in its use of sources and range of themes that it is impossible to isolate a single strength. But I remember being particularly taken with his analysis of the relation between architecture, ritual and social hierarchy—of the ways that the “processional use of space,” of each socially- and gender-defined group entering the church in tern with the male planters entering last as a group, and of the repetition of this pattern at courthouses and planters’ homes, both reflected and reproduced social hierarchy in 18th century Virginia.

Upton began to serve on thesis and dissertation committees at the University of Virginia in 1979, and after a series of visiting appointments in the East, joined the faculty of the University of California, Berkeley in 1983. Over the next 20 years, working in particular with his colleague, Paul Groth, Berkeley became to my mind, the leading center of graduate education in the field. Upton returned to UVA for 5 years, and since 2008 has taught and, for a term, chaired the Art History Department at UCLA. He has served on a total of 150 thesis and dissertation committees, including chairing 29 dissertation committees. His former students constitute a veritable who’s who of second and third generation scholars in the field.

While I am focusing this evening on his books, he has also published over 80 scholarly articles, many as groundbreaking and widely read as his books. “Pattern Books and Professionalism,” Winterthur Portfolio (1983); “White and Black Landscape in Eighteenth Century Virginia,” Places (1985); “Architectural History or Landscape History,” JAE (1991); “Just Architectural Business as Usual,” Places (2000, a critique of New Urbanism) come quickly to mind. Scholars with other interests might come up with an entirely different list of favorites, so broad have been Upton’s concerns.

His 1998 publication Architecture in the United States incorporated recent vernacular architecture and cultural landscape scholarship into an architectural history textbook, deemphasizing the traditional distinction between elite and vernacular. In place of an inclusive chronology, he devoted each chapter to an interpretive theme: Community, Nature, Technology, Money and Art. Another City: Urban Life and Urban Spaces in the New American Republic, from 2008 is a compelling evocation and interpretation of lived experience, of the sights, sounds and smells of the early American cites. Upton notes elite attempts to foster decorum and shape new urban environments, but also elaborates the counter forces of commerce, vernacular social traditions and the demimonde.

Dell Upton has been the recipient of a Guggenheim Fellowship, the John Hope Franklin Prize from the American Studies Association, both the Alice Davis Hitchcock Award and the Spiro Kostof Award from the Society of Architectural Historians, and twice the recipient of the Vernacular Architecture Forum’s Abbott Lowell Cummings Award. Please join me in welcoming the recipient of the 2015 Henry Glassie Award, Dell Upton.

2013 John Michael Vlach

These remarks were delivered by Dell Upton at the VAF annual meeting in Gaspé-Percé, Quebec, Canada:

These remarks were delivered by Dell Upton at the VAF annual meeting in Gaspé-Percé, Quebec, Canada:Appropriately, this recipient of the Henry Glassie Award was a doctoral student of Glassie’s at Indiana University. I first met John at a Folklore Institute party in Bloomington, where he was just finishing his dissertation. He once told me that his interest in African and African American topics went back to his undergraduate days at the University of California at Davis when, as a somewhat directionless football player, he was assigned to a wheelchair-bound faculty member who specialized in African studies. That job showed John his vocation.

The first product of John’s lifelong research project was his 1975 dissertation on the shotgun house. Along with the articles that spun off from it in Pioneer America and Natural History, it was a landmark in many ways. In tracing the history of one of the most common house types of the southern United States, John became the first to take seriously, and to define clearly, the role of Africans and African Americans in the shaping of American architecture. The dissertation was based on an ambitious program of fieldwork in Nigeria, Haiti, and the United States, thus making it a pioneering example of a transnational approach to architectural history, one reinforced by his wonderful Journal of American Folklore article on Brazilian houses in Nigeria.

Although John never published the shotgun house work as a book, it was the seed of two decades' worth of trailblazing field studies of African American landscapes and material culture in the South. When I first knew him, John was always setting off on another research trip, another collecting trip, another visit to a builder or a folk artist. He always seemed to know where the important artifacts were, who the important informants were, and what the important questions were. This work gave us an exhibition and book, The Afro-American Tradition in Decorative Arts, which is still a standard reference in the field. It was one of the first scholarly examinations of black traditions in ceramics, textiles, and woodworking as well as architecture. This work gave us Charleston Blacksmith, his ethnographic study of Philip Simmons, which called attention to Charleston’s long history of African-American smithery, in addition to introducing a master ironworker to a broader audience. And this work gave us his many essays collected in By the Work of Their Hands, a series of articles on Afro-American folk arts and crafts.

In recent years, Vlach has spent as many hours in the archives as he once did in the field. As someone with the good fortune to live near the Library of Congress and to have a wife who is a key official of the Division of Prints and Photographs, John took advantage of the opportunity to mine the records of the Historic American Buildings Survey. The result was Back of the Big House, a study that used HABS's documentation of long-vanished Southern buildings to paint a comprehensive portrait of the built landscape in which enslaved people lived and worked. It is worth noting that when a parallel exhibition of the same name was mounted at the Library in 1995, a firestorm of protest led to its being removed. But the District of Columbia public library recognized the show’s significance and showed it there. The reading public also found that the book told a story they were eager to hear, and as a result Back of the Big House has remained in print for twenty years. I can say with some envy that I can count on one hand the number of museum gift shops that I have visited in the South that did not carry Back of the Big House.

Vlach’s interest in the landscape of plantation slavery led him to examine the records that painters of Southern scenes left behind, and produced The Planter’s Prospect, an important study of the artistic record of slavery. Here John combined his interest in the black experience with a fascination with folk painting expressed most notably in Plain Painters.

John’s enthusiasm for his work has been contagious. As a long-time professor of American Studies and Anthropology at the George Washington University, he was been a popular teacher and mentor of undergraduate and graduate students. He introduced them to a broad spectrum of the American material world, but also gave them a taste of the larger context in which their studies took place. Many years ago, I attended one of his vernacular architecture classes at George Washington University. His invited guest was Arthur Raper, a man now nearly forgotten, but who wrote eye-opening books in the 1930s about sharecroppers and about lynching. I was impressed.

As an assiduous and prolific public folklorist, Vlach gladly shared his work with anyone who would listen. He consulted with museums and historical agencies, curated exhibitions, lectured widely to popular audiences, and even appeared on C-Span several times.

As a pioneer student of African American architecture and material culture, John Vlach’s career has been a model of the kind of scholarship that the VAF was created to encourage, and it has been a model, as well, of engagement with a broad audience of the sort likely to spread our message most effectively. For these and many other reasons, we thank him with this year’s Henry Glassie Award.

2012 Ridout and Tishler

In 2012, Orlando Ridout V and William H. Tishler each received a Henry Glassie Award for lifetime achievement.

Orlando Ridout V

A version of these remarks was delivered by Marcia Miller at the VAF annual meeting in Madison, Wisconsin:

The people in this room most likely fall into two categories. First, there are those who have known and worked with Orlando Ridout V for up to four decades, who will remember and laugh at the stories that are told about him (or by him) and who know what Orlando has done for the study of vernacular architecture over the course of his career. Second, there are those who may know Orlando, but not well, those who may have heard the name, or maybe those who have not. But all of us, regardless of whether or not we know Orlando personally, have been influenced by his approach to fieldwork and scholarship in the seventeenth-, eighteenth-, and early nineteenth-century Chesapeake, including his dedication to understanding technological innovations, building practices, agricultural systems and changing social conventions. His contributions to this field have redefined how we, as a profession, look at buildings. Not content to simply maintain the status quo, he has elevated the standards of our field, continuously working towards bettering our understanding of buildings, refining our documentation standards and rethinking the types of questions we should ask about the built environment.

Orlando’s contributions are expansive, and their seeds were sown more than thirty years ago. He was there at the beginning of our discipline of vernacular architecture studies. He was part of the "Friends of Friendless Farm Buildings," a group of young architectural historians in the Chesapeake region who met informally to share their work, the only requirement of membership being a passion for agricultural buildings and a willingness to share drawings and discoveries. This collaboration not only gave birth to the system of drawing conventions that are used for field documentation to this day, it also was the germ for something much greater. In the fall of 1979, Orlando was one of a small group that established a new organization dedicated to the interdisciplinary study of the built environment, particularly historic architectural resources and their relationship to local culture: that new organization was the Vernacular Architecture Forum.

Among Orlando’s publications stand landmarks that have helped redefine the study of the built environment. His 1989 book Building the Octagon, a study of the design and construction of one of the nation’s first architect-designed townhouses, built in Washington D.C. for John Tayloe III from 1799-1802, has been called "the standard for how single-house studies should be written." It garnered VAF’s Abbott Lowell Cummings Award in 1990. Orlando’s article "Re-editing the Architectural Past: A Comparison of Surviving Physical and Documentary Evidence on Maryland’s Eastern Shore," established numerically what some of us had suspected about the past: that our view of the historic landscape is dramatically skewed by the fact that only a small percentage of the built resources that populated the past have survived to our time, and those that have are woefully unrepresentative. Yet it is his numerous unpublished single house studies that have subtly changed the work of architectural historians and museum professionals. Starting with the Russell House in Charleston, he established a systematic approach based on the assumption that thoroughly understanding a building is critical to its proper care and interpretation. Thus, the seemingly endless process of cataloging all the components of a building down to its nails, assessing the dates of these parts, the nature of their manufacture and use, is essential to answering all of the important questions that must be asked of an historic resource. Layered onto this and just as important is the need to carefully scour the record for all documentary material related to a building’s existence and creating a similar catalog of all known images organized in chronological order. Once assembled, these studies become the basis for interpretive essays that summarize the historical importance of the people who lived and work on these sites and a companion study about its architectural importance.

Looking beyond the building, Orlando has long shown interest in the landscape and the relationship of the house to its surroundings, especially the various parts of a farmstead.

Orlando’s chapter in the soon to be published book Chesapeake House addresses the relationship of the component parts of a farm, how people chose building sites, and how agricultural practices changed the land. To quote Willie Graham, the chapter "will transform the way historians think about early settlement practices and how they matured over the next few hundred years…it will surely become a staple read of archaeologists and historians of all stripes."

Orlando’s career took him into public service, following a long family tradition of service to the State of Maryland that includes two royal governors, members of the Maryland Legislature and the state’s first historic preservation officer. For thirty years, through his own fieldwork and through the statewide survey program that he nurtured into one of the most successful in the country, Orlando has helped compile for Maryland a catalog of its historic resources, founded on his own careful approach of looking at properties as artifacts. This catalog, the Maryland Inventory of Historic Properties, forms the basis of almost all preservation activity in Maryland.

Perhaps his greatest legacy, however, is as a teacher and mentor. Orlando’s work at the State of Maryland, progressing from field surveyor, to head of the state’s architectural survey program to the chief of the Office of Research, Survey and Registration, has provided him countless opportunities to share his knowledge widely. He gives freely and profusely to anyone who is passionate about buildings, and he is especially dedicated to those who desire to become field surveyors. How many people in our field have learned the basics about nail chronologies, framing techniques, and hardware while spending a hot day in a tobacco barn or cold, snowy day in an abandoned eighteenth century house with him? Benefitting in a special way are his students who took his legendary course, "Field Methods for Architectural History" at the George Washington University.

But these examples do not do justice in any way to Orlando’s expansive generosity with the fruits of his intellect and his labor. No matter how elementary or complex the question might be, nor how many times he has answered it before, he always answers with thoughtfulness, unselfishness and modesty. Time and again even the simplest of questions will receive a five-page response which despite being so well-researched and carefully composed that it could go straight to publication without editing, invariably is prefaced by an apology that he couldn’t do more.

Most of us already know that Orlando’s contributions to the field go beyond the professional. His friendship, loyalty, sense of humor and his incomparable ability to tell stories, both of his own colorful adventures and those from this organization’s early days, are part of the heart and soul of VAF. It is with great pleasure that I present the Henry Glassie Award to Orlando Ridout V.

William H. Tishler

These remarks were delivered by Arnold R. Alanen at the VAF annual meeting in Madison, Wisconsin:

These remarks were delivered by Arnold R. Alanen at the VAF annual meeting in Madison, Wisconsin:

Bill Tishler at the VAF meeting in Madison, Wisconsin, 2012

The 2012 Henry Glassie award winner is William (Bill) Tishler, an Emeritus Professor of Landscape Architecture at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Bill played an important role in the early history of VAF, including serving as president in 1982, and as organizer of the 1983 conference in Madison. His numerous publications and field work that featured the folk and vernacular architecture of the Midwest notably stovewood buildings and German-American fachwerk construction dgreatly increased our understanding of ethnic building and landscape traditions.

To best understand Bill, however, one needs to recognize that he is a product of Door County the picturesque peninsula of northeastern Wisconsin that juts into Lake Michigan. Door County is nationally recognized for its natural and cultural attributes, and it shaped Bill both as a person and a scholar. In addition, Bill’s father was a local carpenter, a quite appropriate trade for someone with the German name of Tishler (Tischler).

Following high school Bill made his way to the University of Wisconsin-Madison, where he fortuitously discovered the field of landscape architecture. In 1965, shortly after receiving a Master of Landscape Architecture degree from Harvard’s Graduate School of Design, Bill returned to his alma mater and began teaching at the UW-Madison. During his early career as a faculty member in the Department of Landscape Architecture Bill was asked to prepare a master plan for Old World Wisconsin (OWW), the outdoor ethnic museum then being proposed for the state. Working primarily with students, Bill and his assistants developed the overall OWW plan and also prepared proposals that defined the spatial organization of individual ethnic farmsteads. When OWW opened in 1976 the project was immediately recognized for its sensitive treatment of environmental and cultural phenomena; indeed, the plan soon received a national honor award from the American Society of Landscape Architects.

Among several other notable projects that Bill undertook during his career was the preparation of a preservation plan for the Lake Superior shoreline community of Bayfield, one of Wisconsin’s premier tourist destinations; and a National Historic Landmark nomination for the Namur Belgian District in northeastern Wisconsin, the first NHL property to recognize a rural ethnic group. During the 1990s he and I worked with several graduate students at Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore in Michigan, where we prepared some of the first cultural landscape reports for the National Park Service.

Bill also taught courses on historic preservation methods and practice, including the first in the nation to feature cultural landscapes. A number of students who enrolled in those classes subsequently went on to careers in state and local planning agencies, consulting firms, and academic departments. Certainly among Bill’s important instructional activities were the summer field schools that he organized and directed during the 1970s, all of which documented historic buildings and landscapes in several areas of Wisconsin.. That tradition was revived during this century when three field schools, organized and taught by Anna Andrzejewski and others, contributed so significantly to the field guides that were prepared for the 2012 VAF conference in Madison.

Following his retirement in 2000, Bill taught the first on-line course survey course in the Department of Landscape Architecture, prepared a DVD on the career of Jens Jensen, and wrote a history of Door Country’s Peninsula State Park. For his decades of activity furthering the cause of the Vernacular Architecture Forum, and documenting the buildings and landscapes of Wisconsin and the Midwest, Bill Tishler is a most worthy recipient of the 2012 Henry Glassie award.

2011 Thomas Carter

A version of these remarks was delivered by Boyd Pratt at the VAF annual meeting in Falmouth, Jamaica:

A version of these remarks was delivered by Boyd Pratt at the VAF annual meeting in Falmouth, Jamaica:The Henry Glassie Award, named for the renowned vernacular architecture scholar and folklorist, recognizes special achievements in and contributions to the field of vernacular architecture studies. It is awarded intermittently, as deemed appropriate by the VAF Board of Directors. This year the VAF Board of Directors has deemed it appropriate to present the Henry Glassie Award to Thomas Carter.

Tom Carter is not unfamiliar to members of the VAF. He has served on the board many years, including a stint as President. Many of you may have gotten to know him better, as I did, when he hosted the VAF conference in Salt Lake City, Utah, in 1987. And he has been coeditor of our Special Series: Vernacular Architecture Studies; indeed, he, along with Betsey Cromley, wrote the inaugural publication, Invitation to Vernacular Architecture.

Born in Utah, Tom came East to attend Brown University they nicknamed him "Tex," a stereotypical confusion that Tom would soon work to set straight in his subsequent career. After a Master’s in American folklore from University of North Carolina (Chapel Hill) and a doctorate on Mormon housing in the Sanpete Valley, Utah, from Indiana University (where his original dissertation advisor was none other than Henry Glassie), Tom won a fellowship to the Jeff Klee, Tom Winterthur Museum. There he discovered the growing vernacular architecture movement, and the role he would fill in bringing the American West into that exploration. By 1990, Tom had arrived at the University of Utah's Graduate School of Architecture, as founding director of the Western Regional Architectural Program.

Tom has published many articles, and has co-authored Utah’s Historic Architecture and The Grouse Creek Cultural Survey. Along with Bernie Herman, Tom co-edited Volumes III and IV of Perspectives in Vernacular Architecture, and edited Images of an American Land: Vernacular Studies in the Western United States. I know that we haven’t seen the end of Tom's writing -- he's not dead yet -- and I hope that he will continue to publish his extensive research on the Vernacular Architecture of the American West. One of his long-overdue proposals is appropriately titled Faith and Good Works, something we can take to heart.

I think Tom is best known for his work on documenting vernacular architectural sites through measured drawings. He and his students have ranged throughout the West, Utah, of course, but Nevada and Montana also stand out, and often when I went to a conference I discovered that Tom had been there before, helping to document the structures on the tours. In recognition of this work, Tom received the Buchanan Award in 1996 for his work with the Program for Documenting the Architectural Heritage of the Western United States.

I would be remiss if I did not mention music. Tom began with recording traditional fiddle players in the Blue Ridge Mountains of Virginia, and is an accomplished fiddler himself. I was astounded when we were at the 1988 Staunton, Virginia conference and Tom fell to his knees and began singing "Shenandoah" on the banks of that noble rill.

All of this is quite impressive, and certainly worthy of receiving the Glassie Award. But I want to highlight a significant pattern in Tom's lifetime achievement: his focus on the West. As Chris Wilson once said about the pre-Carter era (I mean Tom, not Jimmy), "There was as much written about the cultural landscape of Virginia as there was on the entire Western United States." Through his meticulous, detailed recording of and research on the vernacular architecture and landscape of the West, Tom has radically changed the way we think about the region and its history. Speaking as a Westerner, a far Westerner, I should add, I have personally and professionally been influenced by Tom’s work, as have we all.

Tom Carter, thank you for your significant achievements in and contributions to the field of vernacular architecture studies. Here's the Glassie Award!

2010 Cary Carson

A version of these remarks was delivered by Jeffrey E. Klee at the VAF annual meeting in Washington, DC:

A version of these remarks was delivered by Jeffrey E. Klee at the VAF annual meeting in Washington, DC:

What can I possibly say about Cary Carson? Intellectual, raconteur, clotheshorse, international man of mystery; founding father of the VAF and presenter of this society’s very first paper. I have known Cary since I came to Williamsburg in 2004. In that time, I’ve come to see him as most of you do: as an insightful, hardworking, elegant writer and a thoughtful, gracious, unfailingly warm individual.

As a scholar, Cary Carson made his mark by insisting that material remains had much to teach us about the past, this much, at least, he shares with Henry Glassie. In 1981, he showed how architecture could be much more than a "handmaiden to history" in his landmark article, "Impermanent Architecture in the Southern American Colonies." Cary and his coauthors observed that architectural form could be correlated with changes in agriculture in a way that was only dimly perceived in the documentary record. They made a strong case for a view of architectural technology as experimental and strategic, rather than instinctive. The essay remains a founding document of modern vernacular architecture studies and shows up on college syllabuses from Salt Lake City to Stalingrad (or as Willie Graham calls it, Petersburg).

Cary has also sustained a lifelong interest in the English ancestry of colonial American architecture and we are all looking forward to the publication of his volume in the VAF Special Series. But his most significant contribution to the study of material life and American history is surely his extended essay, "The Consumer Revolution in Colonial America: Why Demand?" In it, he inverts the presumed relationship between the Industrial and the Consumer Revolutions, arguing that the colonial experience required objects to communicate relationships, and that this growing need spurred the drive to greater production, not the reverse. In his words, "a world in motion was a world of strangers" and these strangers used objects to sort themselves out in carefully delimited ways.

As important as this essay is, and inasmuch as it demonstrates Cary’s mastery of language and of his material, it also exemplifies his commitment to a style of history that engages explicitly with present concerns. Along with the dissertations, scholarly articles, and contemporary diary entries, the 307 footnotes include references to The Washington Post and The New York Times. It is never enough for Cary just to untangle a knotty intellectual problem. His work must always participate in the larger contemporary discourse; its implications must always reach beyond the library. Both his published work and his career at the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation manifest a generous commitment to scholarship as a form of public service.

This generosity is not restricted to his research. Cary is forever eager to share credit, and has demonstrated an almost compulsive preference for working with collaborators over going it alone. As a fieldworker, author, administrator, or bowler, Cary prefers company, the more the better, and thank goodness, because what a delightful companion he is.

As much as he encourages his friends and colleagues, he seems to enjoy provoking them even more. As an editor, a boss, or an invited speaker, he relishes and excels in the role of gadfly, setting sparks to intellectual tinderboxes while stamping out little flare-ups of foolishness. Many members will recall his plenary address in Williamsburg in which he challenged the VAF to slough off the complacency that comes with recognition and success. Others will remember a similar talk at Winterthur, "Material Culture History: The Scholarship Nobody Knows," in which he goaded his audience to engage more effectively with other disciplines and broader audiences. He also, memorably, took the opportunity to critique some colleagues’ fascination with Continental philosophy, suggesting that one, in particular, was so enamored with French thinkers that he should be registered as a foreign agent.

This last item hints at an aspect of Dr. Carson that may be less well known among the VAF but is no less praiseworthy. He is a great connoisseur of mischief. Many have been ruthlessly victimized by the glint in Cary’s eye, not least among them the innocent schoolchildren of Williamsburg, who endure unholy terror every Halloween as they run the gauntlet of Griffin Avenue.

Cary, this organization is intellectually richer and just plain more fun for your involvement in it. I am, therefore, delighted and honored to present you as this year’s winner of the Henry Glassie Award.

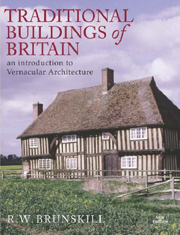

2009 Ronald W. Brunskill

The recipient of the Henry Glassie Award is Ronald W. Brunskill, RIBA, OBE, FSA, in honor of his long and distinguish career in teaching and the promotion of the study and conservation of vernacular architecture in Great Britain and in this country through his many written works and service on numerous historical commissions. Trained as an architect at Manchester University just after World War II, Ronald Brunskill also received his MA and PhD from that institution where he studied under the legendary R. A. Cordingley, who pioneered the study of regional architecture and offered him a job in the School of Architecture where he taught from 1960 to 1989. His academic training may have shaped Professor Brunskill's intellectual perspective, but his passion for vernacular building derived from his early holidays spent on farms of his relatives in the achingly beautiful Eden Valley on the edge of the Lake District. These encounters with stone farmhouses and barns in the region was eventually expanded and incorporated in Vernacular Architecture of the Lake Counties.

The recipient of the Henry Glassie Award is Ronald W. Brunskill, RIBA, OBE, FSA, in honor of his long and distinguish career in teaching and the promotion of the study and conservation of vernacular architecture in Great Britain and in this country through his many written works and service on numerous historical commissions. Trained as an architect at Manchester University just after World War II, Ronald Brunskill also received his MA and PhD from that institution where he studied under the legendary R. A. Cordingley, who pioneered the study of regional architecture and offered him a job in the School of Architecture where he taught from 1960 to 1989. His academic training may have shaped Professor Brunskill's intellectual perspective, but his passion for vernacular building derived from his early holidays spent on farms of his relatives in the achingly beautiful Eden Valley on the edge of the Lake District. These encounters with stone farmhouses and barns in the region was eventually expanded and incorporated in Vernacular Architecture of the Lake Counties.

The pattern of his scholarship was set and would have a tremendous impact in Britain and the United States from the 1970s onward. "Brunskill's Illustrated Handbook of Vernacular Architecture is where we all started" observed Barbara Watkins, Secretary of the English Vernacular Architecture Group. This and others such as Traditional Farm Buildings of Britain, English Brickwork, and Timber Building in Britain have been primers for a generation of amateur recording societies and professionals alike. Their orderly presentation of plans, structural elements, and decorative details emphasize the richness of regional building practices in Britain, but most importantly, opened the sometimes esoteric study of traditional buildings to a broad readership. They emphasize that recognizing and preserving this architectural heritage is not merely the preserve of the scholar but beckons the lay person as well, appealing to an ethos that has not fully blossomed in this country in the way it that has long bloomed among the scores of amateur historical and antiquarian societies in Britain. In the United States we train students in special programs to record historic structures; in the British Isles, men and women from all walks of life come together to spend their weekends and holidays measuring neighboring farmhouses and a Brunskill volume has accompanied them in their kitbag.

Like the man for whom this award is named, Ronald Brunskill has been a highly successful missionary and publicist for vernacular architecture. J. T. Smith, the retired principal investigator for Royal Commission on Historical Monuments, described Professor Brunskill's lectures as "inspiring and beautifully delivered." He recalled that one of them given in the mid 1960s "aroused the audience's enthusiasm to a remarkable degree and made even a seasoned practitioner like myself want to rush out and record whatever lay to hand."

In addition to his academic responsibilities, Dr. Brunksill has more than shared his time as a committee member servicing as an advisor, reviewer, and leader of numerous architectural, antiquarian, and historical commissions and professional societies. He has served as President of the Vernacular Architecture Group, vice-chairman of the Weald and Downland Museum, and has been a member of the Royal Commission on Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales, the Heritage Lottery Fund, and the Friends of Friendless Churches to name but a few on an exhaustive list.

Ronald Brunskill's career bounded the Atlantic in ways that have allowed us to claim him as one of our unofficial founders. His wife Miriam was originally from Georgia and that bond that united our two countries gave rise to his deep interests in America over the past half century. In the mid 1950s hew was awarded a traveling fellowship at MIT and visited the newly reconstructed settlement at Jamestown Festival Park with its collection of cruck buildings that emphasized to him the remarkable limited understanding that Americans had of English vernacular building. Not long to be discouraged, he found an affinity in the farm buildings of Pennsylvania with those in his beloved Westmoreland in the Lake District and he was emboldened to introduce the term "bank barn" to vernacular building in England. In his teaching at Manchester and courses at the University of York he managed to attract American students including Charles Peterson, one of the founding lights of the Historic American Buildings Survey, and organized several exhibitions in England of HABS work.

Professor Brunskill traveled widely in the United States and met most people who were involved in the study of traditional architecture including Jay Edwards, Abbott Cummings, and Blair Reeves. Intriguingly, in the late 1960s he met with John Pearce, Rusty Marshall and others to discuss the establishment of an American organization equivalent to the English VAG but decided that the time was not yet ripe. More than a dozen years later after the VAF was formed, he attended a number of our early meetings including Sturbridge, San Francisco, Santa Fe, and Portsmouth. For a man who has been an instrumental force in shaping the study of vernacular architecture on both sides of the Atlantic, the VAF proudly presents the Henry Glassie Award to Ronald Brunskill.

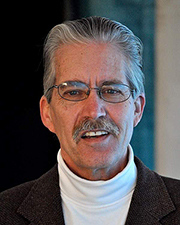

Carl Lounsbury

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation

2007 Ronald Knapp

This year the Henry Glassie Award Committee solicited nominations of books published between 2004 and 2006 that made significant contributions to the study of vernacular architecture and cultural landscapes outside North America. The winner of the 2007 Glassie Award is Ronald G. Knapp. The committee, which consisted of Rebecca Ginsburg, Greg Hise, and Tom Hubka, was interested to see that Professor Knapp had been nominated for two books, Chinese Houses: The Architectural Heritage of a Nation, published by Tuttle Press (2005) and House Home Family: Living and Being Chinese, published by the University of Hawaii Press (2005) (and co-edited by Kay-Yin Lo). Both books were excellent examples of scholarship of vernacular environments. The committee noted that the first was based on over thirty years of fieldwork in China. We were impressed enough with these two volumes to want to see more. After reviewing Asia's Old Dwellings: Tradition, Resilience, and Change (2003), China's Old Dwellings (2000), China's Living Houses: Folk Beliefs, Symbols, and Household Ornamentation (1999), Chinese Landscapes: The Village as Place (1992), China's Vernacular Architecture: House Form and Culture (1989), to name just a selection of Professor Knapp's writings, we realized that this lifetime of scholarship dedicated to documenting, studying, and writing about Chinese domestic architecture for Western audiences deserved recognition. A notable strength of Ronald Knapp's body of works is his comprehensive approach to the study of housing. His books examine scales from that of interior decor to the layout of villages. He considers the role of fengshui in the placement of furnishings and provides extensive discussion of construction techniques and materials. Floor plans, diagrams that illustrate social use of space, village layouts, and historical drawings compliment his texts, which are consistently clear and accessible. Photographs are often stunning, especially in his later works such as Chinese Houses, which is a beautifully designed book (credit goes to A. Chester Ong, who did the photography). Ronald Knapp, who was trained as a geographer, has done more than anyone else outside of China to celebrate, analyze, and promote understanding of that country's domestic architectural heritage. We are pleased to present the Glassie Award to Ronald G. Knapp for the lifetime body of his work on Chinese houses.

2006 Tom Hubka

The Henry Glassie Award Committee, consisting of Dell Upton, Stephen Hornsby, and Rebecca Ginsburg, sought to recognize recently published books that have made significant contributions to the study of vernacular architecture and cultural landscapes outside North America. The VAF awarded the 2006 Glassie Award to Thomas Hubka for Resplendent Synagogue: Architecture and Worship in an Eighteenth-Century Polish Community (University Press of New England/Brandeis University Press, 2003).

In Resplendent Synagogue, Tom Hubka closely analyzes the design and use of an eighteenth-century synagogue in the Polish town of Gwozdziec, in the process uncovering the social, historic, and artistic relations that pertained within a small Eastern European community during the height of its prosperity. While the synagogue no longer stands, Tom Hubka makes critical use of historic photographs, contemporary religious texts, and archival documents, as well as modern scholarship, to reconstruct the history of the Gwozdziec synagogue and place it within its various contexts. These include both a tradition of wooden synagogue construction that was common in Eastern Europe until the 19th century, and the synagogue’s specific location within the Gwozdeziec community, where its designers drew on local and foreign, Jewish and Gentile, folks and fine art traditions in building and decorating the house of worship.

2005 “Big Jim” Griffith

James "Big Jim" Griffith’s lifetime of dedicated scholarship on the cultural landscape of the American Southwest and Arizona/Sonora borderlands region was recognized at the 2005 conference of the VAF in Tucson, Arizona, with the presentation of the Henry Glassie Award. This award, bestowed intermittently by the Executive Committee for special achievements in vernacular architecture studies, went to Big Jim for twenty-five years of researching, publishing, and celebrating the traditional lore, customs, arts, and architecture of this important American/Mexican region. Jim’s publications include Southern Arizona Folk Arts, Beliefs and Holy Places: A Spiritual Geography of the Pimeria Alta, and A Shared Space: Folklife in the Arizona-Sonora Borderlands. He also established the Southwest Folklore Center at the University of Arizona and organized the seminal "Tucson Meet Yourself" festival, which celebrates the food, art, music, and other traditions of the city’s various ethnic communities.

2004 Don Yoder

At the 2004 meeting in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, the Henry Glassie Award was given to Professor Don Yoder of the University of Pennsylvania. Professor Yoder has expanded our understanding of the Pennsylvania Germans through a lifetime of folkloric research on their foodways, customs, religion, and popular politics. His work, disseminated in many books and articles, arises from a fervent attachment to Pennsylvania German culture, but always preserves scholarly and analytical rigor. Professor Yoder was instrumental in starting The Pennsylvania Dutchman and Pennsylvania Folklife journals, and served as mentor to a generation of young scholars who took it upon themselves to document and interpret the varied meanings of the Pennsylvania German cultural landscape and its rich architectural traditions.

1999 Albert Lorenz and David Macaulay

The VAF presented the Special Recognition Award at the annual conference in Columbus, Georgia. The winners were Albert Lorenz and David Macaulay. VAF selected winners whose contribution to the scholarship and appreciation of architecture is unique by virtue of the audience for their work. They write for children.

More importantly, they write and draw splendidly for children. In presenting this award to David Macaulay and Albert Lorenz, the VAF is recognizing that the appreciation for architecture and its historical meaning can and should begin early. Further, in selecting these two authors, we hope to encourage excellence in children’s architectural literature–excellence in historical research, intelligent and engaging historical narrative, and revealing illustrations.

There could be no better ambassadors to world of children than these two authors. David Macaulay is a name long familiar to parents, educators, and children. Beginning in 1973 with the book, Cathedral, Macaulay has produced a delightful shelf of books on architecture and the world we’ve built around us. From Roman cities in City to modern urban centers in Underground, and from studies of historic mills, in the book, Mill, to sailing vessels, in Ship, Macaulay has illuminated with great clarity, in black and white line drawings, the structures (and infrastructures) of everyday life. David Macaulay has also created a series of videos based on his works that further explore the fascinating world of constructing objects.

Albert Lorenz’s style is entirely different. He uses color, multiple panels, ravishing detail, and selected narratives to show change, diversity, and pattern over time and place. His first work in 1996, Metropolis drew crowds in bookstores. It was followed by the compelling House in 1998. In both books, he worked with Joy Schleh. Lorenz’s work is an example of the highest achievement in the art of informative and seductive illustration. He has given children a rich context for understanding building within cultural, geographical, and historical settings.