Artist-in-Residence Program with the National Park Service

by Harley Cowan

The arts have been a part of national parks for nearly 150 years. I got my shot in September.

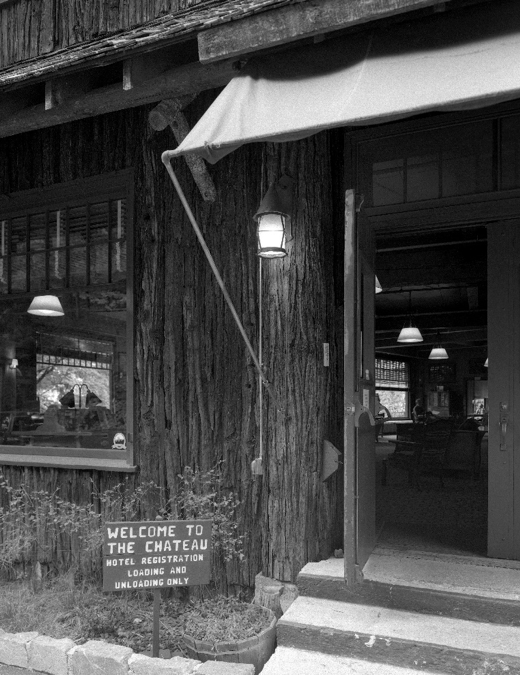

Oregon Caves National Monument and Preserve is one of over fifty parks around the country which offers an artist-in-residence (AIR) program. The programs are open to emerging and established artists of all disciplines and are competitive. Oregon Caves’ residency includes two weeks of lodging in a private apartment within a historic building on site.

My proposal was to photograph the Chateau at the Oregon Caves just prior to its closure for renovation on its 85th birthday. Since the nature of modifications will be character-changing, this seemed like an excellent point in time to make a visual record of the building. The selection committee agreed.

So, with a carton full of black and white sheet film and large format camera in hand, I made the journey to southern Oregon to spend a fortnight living and working with rangers and staff at the monument and preserve.

The West has no shortage of iconic, rustic lodges and the Chateau at the Oregon Caves is no exception. Built between 1931 and 1934 by local architect Gust Lium, it is sited over a small gorge where the River Styx, as it is called, exits the mouth of the Oregon Caves.

The lodge is a six-story, heavy timber structure clad in Port Orford cedar which retains its bark giving the exterior a rough, shaggy appearance that blends in with its surroundings. Its upper stories sit beneath steep gable-ended roofs with long shed dormers that are broken up by more gables.

Retaining walls and a pond were built with stone from the site by the Civilian Conservation Corps immediately after construction was completed on the lodge. The creek fills the pond, then travels lazily through the chateau’s dining room before continuing on its way downhill. For a time, the pond was stocked with trout.

Deep balconies once spanned the downhill side of the building but, as they were not designed to handle snow loads, they eventually had to be removed. They were replaced with fire escapes made of narrow wooden catwalks with pipe railings and metal stairs.

The interiors are dominated by a frame of enormous square timber beams and round columns. Walls are finished in redwood wainscoting with pressed fiberboard above and on the ceilings. The lobby features a double-sided fireplace made of marble that was blasted out of the hillside during construction. All other heating throughout is by steam radiators.

The lobby is still furnished with its original Mason Monterey wooden tables and chairs made by the Mason Manufacturing Company of Los Angeles. The Chateau’s collection represents the world’s largest single assembly of this style of arts and crafts furniture.

The dining room on the third floor was designed with a portion of the River Styx, diverted from the pond outside, brought through. In 1936, a flood rushed through the breezeway of the adjacent Chalet and into the Chateau. The force of the flood moved the heavy timber structure seven inches off its foundations. Bulldozers and chains were used to gradually pull the building back, an inch per week over two months.

Storage space on the third floor was converted into a coffee shop in 1937. A long serpentine counter with swivel chairs were installed in 1954 to double the previous capacity. A post was also added to support a beam cracked by the earlier flood. The design provides servers with easy access to a large number of customers as well as an abundance of cabinets. I noticed that it also inspired socialization amongst strangers.

Up to this point the Chateau has survived largely unchanged. New lavatories and light fixtures have been installed in many of the rooms. Some of the wooden floors have been carpeted and several spaces are populated with incongruent furnishings but, overall, guests experience it very much as one would have during its period of significance.

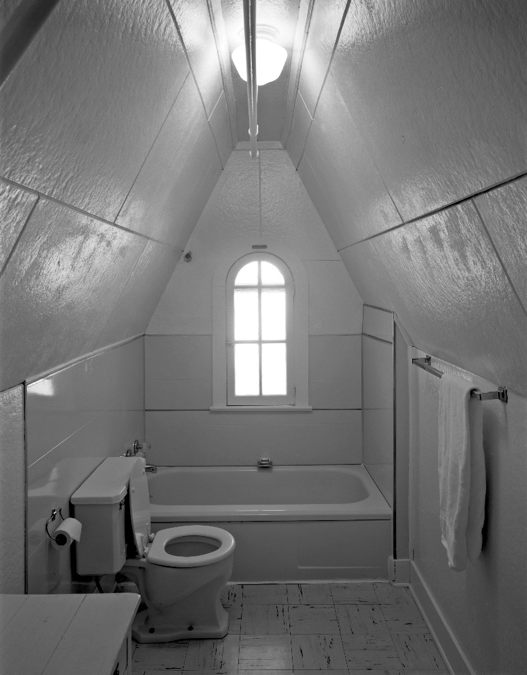

The twenty-three guest rooms vary widely in shape and configuration. Fourth and fifth floor rooms are generally more spacious while rooms on the top floor reflect the geometry of the roof.

Corridors are extremely narrow, rooms are tight, and accessibility is a challenge. Steam heat is more effective in some parts of the building than others. And yet these characteristics are part of what makes the building, and the experience of staying here, so compelling. It will be interesting to see if the planned renovations will be able to retain the personality of the lodge or will wash it away.

One of the goals of the residency program is for the artist to interact with the general public. This is self-directed and can take a variety of forms. Since setting up a large format camera is intensive and deliberate, and visitors were invariably curious, I gave impromptu demonstrations as I worked. I explained the process and let people get under the blackout cloth to see the image on the ground glass. We talked about the extreme resolution of a large format image, the archival permanence of black and white film, and the importance of keeping a physical artifact as part of the historical record.

One of the goals of the residency program is for the artist to interact with the general public. This is self-directed and can take a variety of forms. Since setting up a large format camera is intensive and deliberate, and visitors were invariably curious, I gave impromptu demonstrations as I worked. I explained the process and let people get under the blackout cloth to see the image on the ground glass. We talked about the extreme resolution of a large format image, the archival permanence of black and white film, and the importance of keeping a physical artifact as part of the historical record.

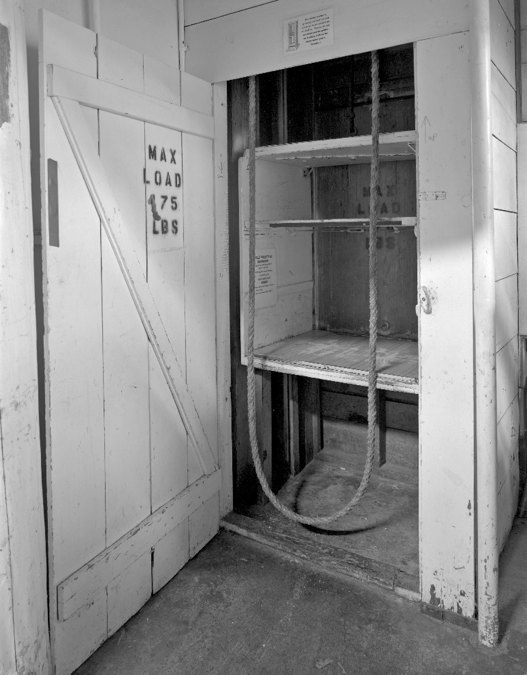

I treated my time as a documentation project but, since the purpose of the residency is to provide time for creative reflection and experimentation, I did not strictly follow the HABS guidelines. In addition to public spaces, I was able to explore the basement levels where the storage, plumbing, maintenance, and boiler room are where I made some long exposures with available light.

Historic documentation is often triggered by renovation or mitigation. Consequently, budgets and schedules for record making are driven by factors that have little to do with the long-term importance or value of the historic record. The residency offered a luxury of time and focus that I have not had with other documentation projects.

Harley Cowan

2018 Access Award winner

Website: www.harleycowan.com

Instagram: @harleycowan