by David S. Rotenstein

Historic preservation and social impact analyses are hardwired into most environmental review regimes, from state and local laws all the way up to the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA). Sometimes concerns for old buildings and spaces intersect with interests in daily lives of people living in communities affected by projects that may disrupt them — new roads, railroads, dams, and pipelines, for example. A historic bridge and a Jewish eruv are located at one such intersection along a light rail line under construction in the Washington, D.C., suburbs.

The Purple Line is a 16-mile light rail project connecting communities in Montgomery and Prince George’s counties, Maryland, north of the District of Columbia. Because the Maryland Transit Administration is using federal funding to build the project, the agency had to comply with the Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA) and NEPA. By the time that the Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) was completed in 2014, several potential social justice and social effects had been identified along with several properties eligible for listing in the National Register of Historic Places. Historic properties included a twentieth century garden apartment complex, parkways, and the former Baltimore and Ohio Railroad corridor. Disruptions to local transportation networks, economic impacts, and displacement were among the social impact issues identified.

The Purple Line implemented plans to mitigate these impacts and construction began in 2017.

As with all large-scale projects, unanticipated impacts were identified after project proponents completed the EIS. The Talbot Avenue Bridge [PDF] is a property that had been determined eligible for listing in the National Register for its association with the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad as an engineering structure. Located in Montgomery County and completed in 1918, the metal girder bridge formed a vital link connecting a historic African American hamlet with unincorporated Silver Spring and Washington, D.C. Samuel Lytton, a free man of color founded Lyttonsville in 1853 when he bought four acres and began farming there. Silver Spring was a sundown suburb where African Americans could not buy or rent homes; Jim Crow also erected barriers to patronizing many of the businesses located there.

Lyttonsville endured more than a century of environmental racism and the social costs imposed by housing segregation and its corollary, concentrated poverty. Urban Renewal in the 1970s disrupted the community and in the second decade of the twentieth century, suburban retrofitting and gentrification threaten to complete the erasure that white Montgomery County residents and leaders had sought for more than half a century.

In the early 1960s, observant Jews began moving from nearby Washington into the suburbs. Like their white non-Jewish counterparts, they were fleeing African Americans moving into neighborhoods once segregated by racial restrictive covenants and they were looking to enjoy the American dream of living in the suburbs. Like African Americans, Washington Jews also enjoyed more consumer choices in the housing market after the U.S. Supreme Court in 1948 ruled racial restrictive deed covenants unenforceable.

![Summit Hill apartments (later renamed Summit Hills], 2017. Developed and owned by Washington Jews, the complex was completed in 1963. Summit Hill apartments (later renamed Summit Hills], 2017. Developed and owned by Washington Jews, the complex was completed in 1963.](/resources/Pictures/VAN/19-1/SummitHills-2017.JPG)

One of Montgomery County’s earliest concentrations of Jewish households formed next to Lyttonsville. A large number of Jews moved into a new apartment complex and in 1963 founded the congregation that came to be known as the Woodside Synagogue. Many Jews also began buying single-family homes in nearby subdivisions. The proximity to synagogues just over the District line and to new ones in Silver Spring quickly made the area attractive to other Jews. More synagogues followed as the population grew in the 1960s and 1970s. The Washington metropolitan area (including the District of Columbia, Maryland, and Virginia) has about 300,000 Jews; the southern part of Montgomery County has about 86,000 according to a 2017 Brandeis University study.

The Purple Line cuts through this space shared by African Americans and Jews. The Talbot Avenue Bridge’s social history and Silver Spring’s Jews were completely absent from the Purple Line’s environmental studies. I stumbled into the intersection of these two issues in my research on erasure, displacement, and how history and historic preservation are produced in American suburbs.

My first article on the bridge appeared in my blog in early September 2016. Washington Post articles and other media coverage followed. By early 2017, people well beyond Lyttonsville knew about the bridge and how it connected the sundown suburb to the other side of the tracks. Residents in the previously all-white North Woodside (east of the tracks) and Lyttonsville began collaborating on ways to celebration the bridge’s history before its demolition in early 2019. In April 2018 I curated a pop-up history museum on the bridge rails and deck. Five months later, neighbors threw centennial birthday party for the bridge that included live music, art, and speeches on the communities’ histories. More than 200 people were there when the president of North Woodside’s civic association read a proclamation from his board of directors renouncing his neighborhood’s earlier racism and pledging to work more closely with their neighbors across the tracks. The event amplified the bridge’s voice and enabled even more people to learn about its history.

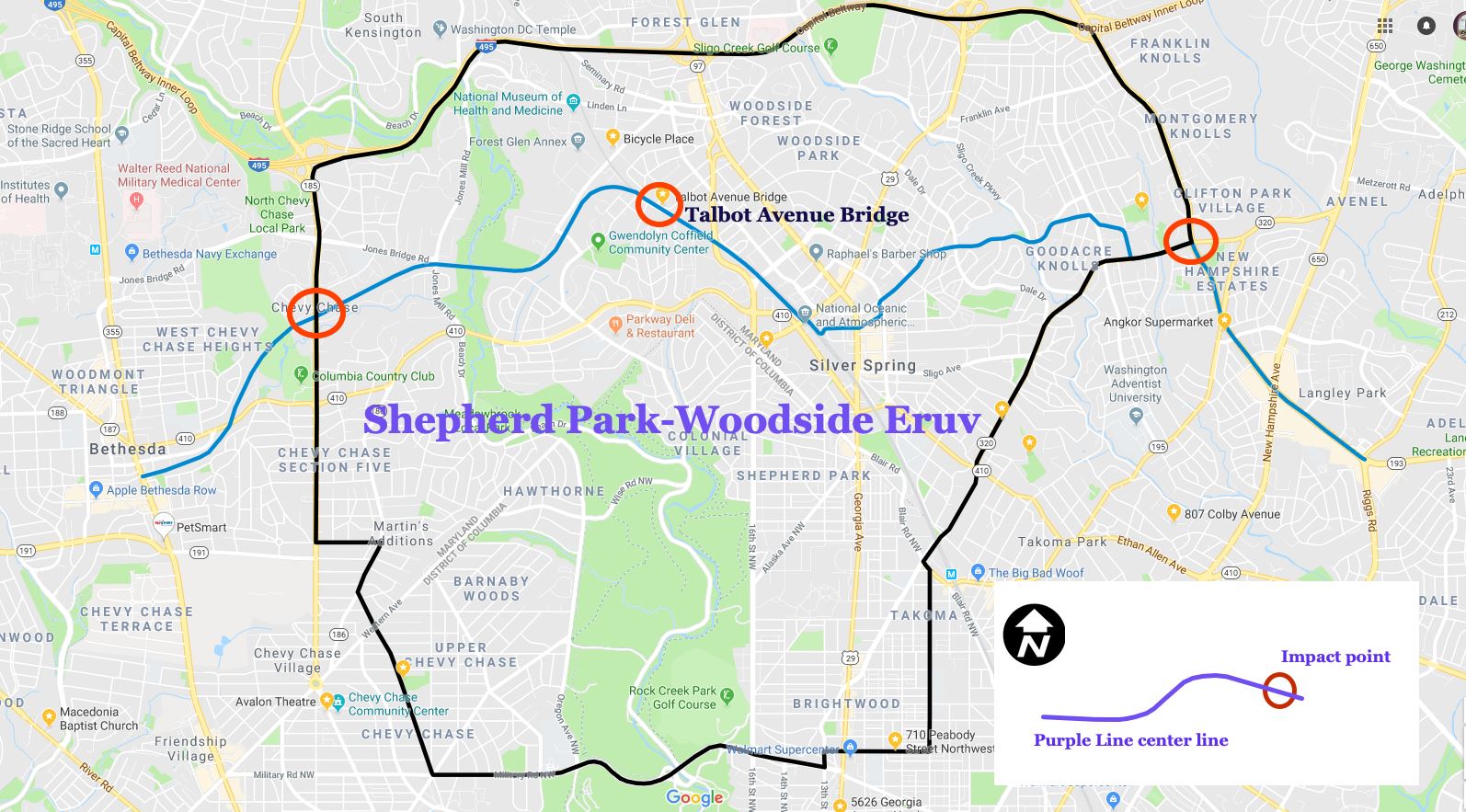

As these efforts were underway, Purple Line construction was moving forward. By the fall of 2018, observant Jews living in Lyttonsville and Rosemary Hills began worrying about how they would get to the Woodside Synagogue. Jewish law prohibits driving and many of the Jews living in these neighborhoods intentionally moved there because of the direct walking route to synagogue. The bridge and synagogue are located inside the Shepherd Park-Woodside Eruv, a 12-square-mile enclosure that enables observant Jews to use medical devices like canes and walkers, push strollers, and carry food and books during the Sabbath.

Silver Spring’s Jews, like the bridge’s ties to Black history, were invisible to Purple Line planners. Other transportation departments have consulted with local Jewish communities when projects might impact eruvs. In Georgia, transportation officials in metropolitan Atlanta coordinated with a synagogue to ensure that its eruv boundary remained unbroken during construction. And in Savannah, an eruv was evaluated as a traditional cultural property and initially was determined eligible for listing in the National Register of Historic Places. In Dallas, Texas, light rail planners [PDF] there worked closely with a Jewish community to protect its eruv.

Besides disrupting walking routes to synagogue, the Purple Line intersects the eruv in two places, where it enters in the east and where it exits in the west. Rabbis and eruv managers affiliated with the Woodside Synagogue and Washington’s Ohev Sholom said in interviews that no one from the Purple Line consulted with them.

Meanwhile, the Talbot Avenue Bridge occupies a space where Silver Spring’s Black history intersects with its Jewish history. It is a space where people and histories have been rendered invisible. My ongoing research and collaborations with these communities derives from research begun in the Washington suburbs and published in VAN in 2011 (“Courtyards of Convenience: Montgomery County’s Eruvs.”). My focus shifted to gentrification and erasure after 2011 with work on my forthcoming book about Decatur, Georgia. It continued after 2014 was I returned to Montgomery County in search of comparative data. And, it has come full circle with my work on the Talbot Avenue Bridge — a site where erasure, eruvs, displacement, and the imperfect ways in which history and historic preservation are produced converge.