by Janet Sheridan

In the Winter 2016 issue of the VAN, I presented some preliminary findings about four farm outbuildings I was studying in Salem County, New Jersey, with the help of an Orlando Ridout V Fieldwork Fellowship and a research grant from the New Jersey Historical Commission. In April, I completed the report, entitled “Salem County Farms Recording Project Vol. II.” Following are some concluding thoughts.

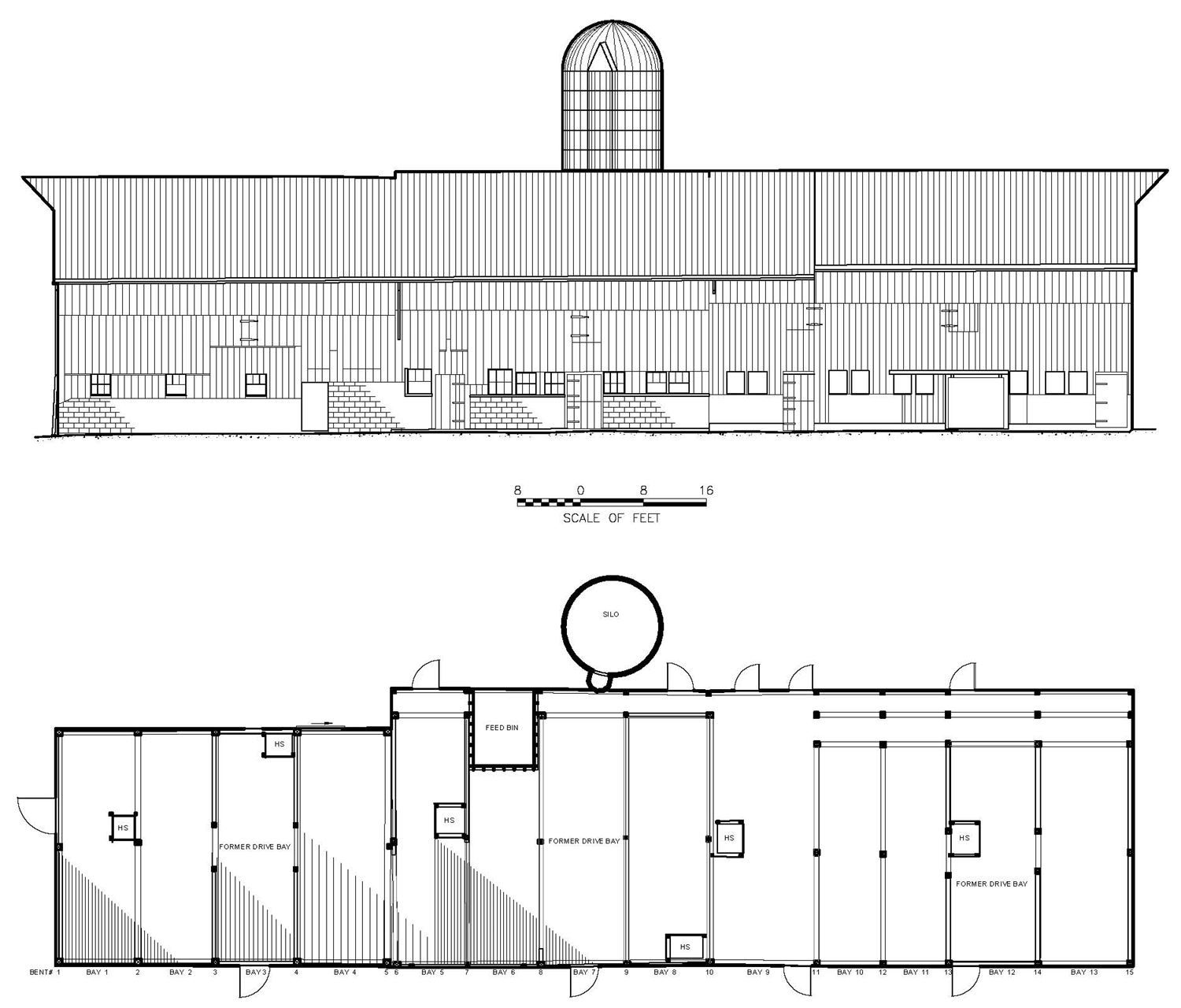

My research revealed an example of a four-bay English barn in which a barn built in 1792 was copied twice more by 1860 as Quaker farmers named Bassett and Allen expanded their capacity to stable livestock and store fodder. Two barns were moved end-to-end and a third was built some 13 feet away, all measuring close to 40x30 feet in plan, and all hewn oak frames with threshing bays. Immigrant Quakers from Bucks County, Pennsylvania named Cadwallader expanded the dairy operation in 1938, further adapting these old barns to their needs by connecting all three together, expanding two of them laterally (to comply with dairy regulations), and using the third for stabling work horses behind a separating sliding door. Though their milking days are over and the horses are gone, the barns continue to house heifers. These barns are a twist on the well-known three-bay English threshing barn, the traditional and ubiquitous Eastern idea having evolved into a taller, four-bay version between 1792 and 1848 and persisting into the late nineteenth century.

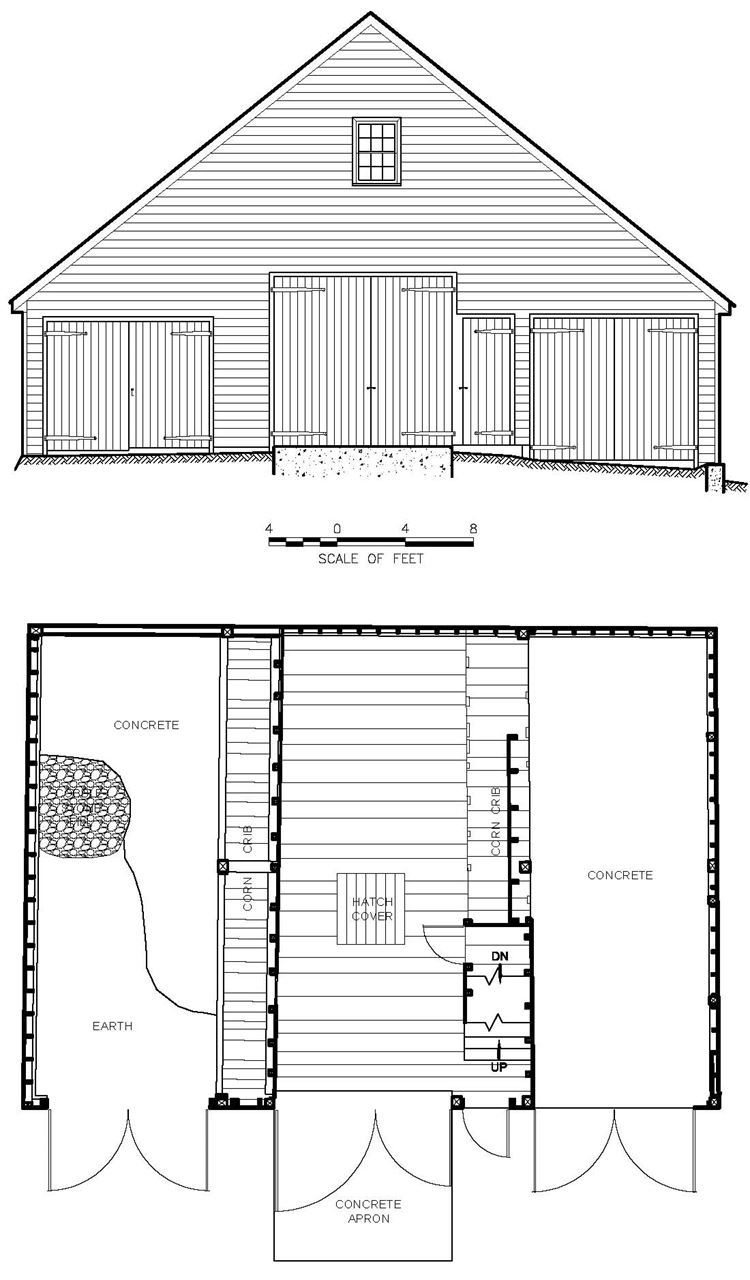

Wagon houses seem to have been ubiquitous as English barns on the farmsteads of the county. Typically they are situated closest to the house of any outbuilding, have a gable-end orientation, a central bay with loft and sometimes a cellar, and two flanking side-aisles. They are reminiscent of Dutch, New England, Midwestern or Appalachian barns. But their use is distinctly different. These buildings are not the main barn, that is, the large one that was designed for threshing, animal stalling, and hay storage. They are multi-purpose storage buildings that hold corn, root and orchard crops, grain, sometimes meat, and wagons and implements, but do not house animals. They seem to appear by 1850, perhaps due to the early nineteenth-century expansion of farming and the need for more secure, and observable, storage space. Some are built of a piece (looking very Dutch with continuous roof slopes), and others accrue their side aisles over time with broken roof slopes. The Zerns-Wright wagon house is an example of the former type, built of a piece with a central stone cellar for seed potato storage, corn cribs in the central bay, and a granary loft finished with tight-fitting boards to keep out vermin. A sturdy staircase and floor hatches facilitate loading and unloading of produce to and from loft and cellar.

Wagon houses seem to have been ubiquitous as English barns on the farmsteads of the county. Typically they are situated closest to the house of any outbuilding, have a gable-end orientation, a central bay with loft and sometimes a cellar, and two flanking side-aisles. They are reminiscent of Dutch, New England, Midwestern or Appalachian barns. But their use is distinctly different. These buildings are not the main barn, that is, the large one that was designed for threshing, animal stalling, and hay storage. They are multi-purpose storage buildings that hold corn, root and orchard crops, grain, sometimes meat, and wagons and implements, but do not house animals. They seem to appear by 1850, perhaps due to the early nineteenth-century expansion of farming and the need for more secure, and observable, storage space. Some are built of a piece (looking very Dutch with continuous roof slopes), and others accrue their side aisles over time with broken roof slopes. The Zerns-Wright wagon house is an example of the former type, built of a piece with a central stone cellar for seed potato storage, corn cribs in the central bay, and a granary loft finished with tight-fitting boards to keep out vermin. A sturdy staircase and floor hatches facilitate loading and unloading of produce to and from loft and cellar.

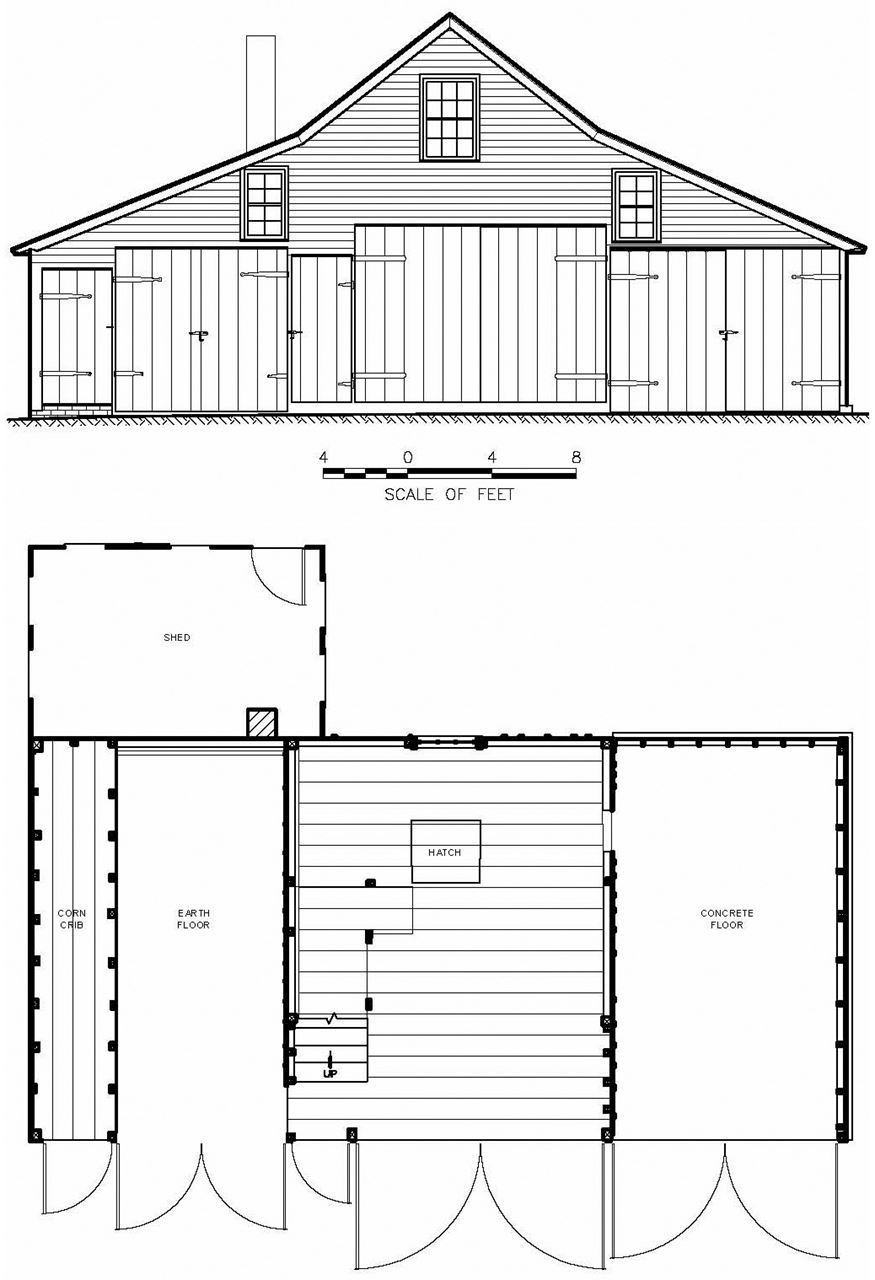

In contrast, the Stretch-Mulford wagon house grew out of a single-purpose one-story granary (the first I’ve found), originally 15x14 feet in plan, in multiple builds. It first grew upwards a half-story, adding grain bins to the loft (which survive), then it sprouted a side aisle below the main roof. It was converted to a wagon house with a 3-foot front expansion and by lowering the floor to the ground. Another side aisle was added, and both aisle roofs were raised to lay on top of the main roof, creating the distinctive broken slope. Only in the early twentieth-century was a corn crib added in one of the aisles. In several generations, it arrived at the common form that usually begins as a single-bay drive-in crib house versus a granary.

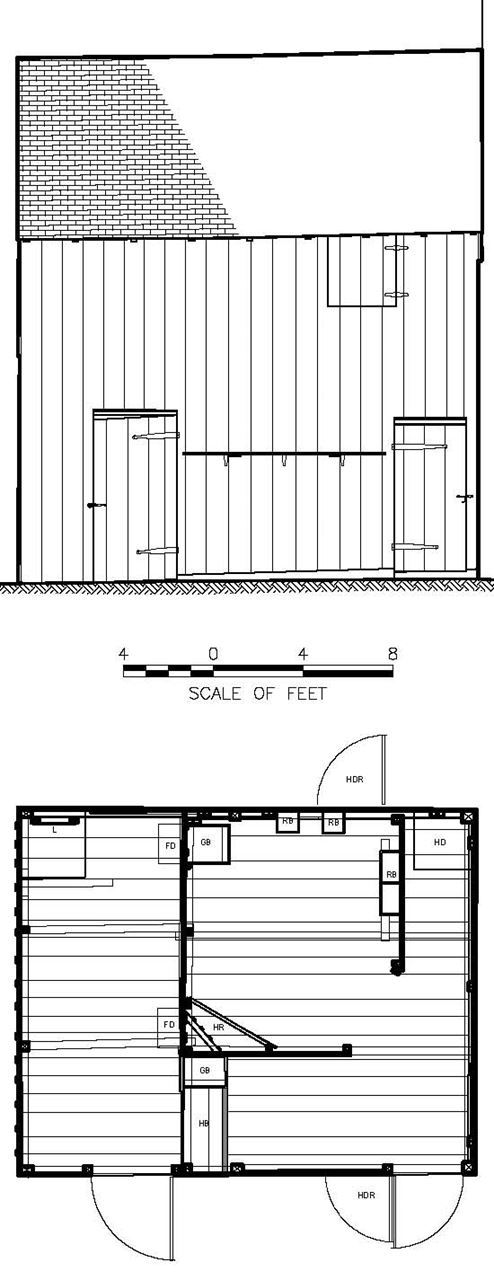

The 16x20-foot plan Stretch-Mulford carriage barn is a diminutive version of a ground barn built as early as the 1840s. Two structural bays accommodated a carriage and horse stalls. Like the wagon house, it is situated prominently in the farmyard, next to the wagon house with matching board-and-batten siding. Its appearance may be more of an urban phenomenon; I’ve seen few farm buildings that resemble this one. Its proximity to the City of Salem (only 800 feet outside its limits) may have influenced its affluent owner to build it.

The 16x20-foot plan Stretch-Mulford carriage barn is a diminutive version of a ground barn built as early as the 1840s. Two structural bays accommodated a carriage and horse stalls. Like the wagon house, it is situated prominently in the farmyard, next to the wagon house with matching board-and-batten siding. Its appearance may be more of an urban phenomenon; I’ve seen few farm buildings that resemble this one. Its proximity to the City of Salem (only 800 feet outside its limits) may have influenced its affluent owner to build it.

The report, organized as a New Jersey Cultural Resource Survey, is available for viewing and/or downloading at https://issuu.com/jlsheridan/docs/salem_county_farms_recording_projec (note this is a revised version). Full-size measured drawings are included inside the report. Volume I, a study of three farmsteads, can be accessed at https://issuu.com/jlsheridan/docs/farms_recording_survey_report.

Many thanks to VAF for the fellowship support of this research!