by Megan Scott, BOLA Architecture + Planning

The Hori Furoba (or Bathhouse) located in King County, Washington, proximate to the small city of Auburn, is a traditional Japanese domestic building. It was built by the Hori family in 1930, and was a part of the family’s daily routine throughout the 1930s when they resided in the nearby Neely mansion. The Horis were among the Japanese-Americans who were interned during World War II. Subsequent, non-Japanese owners of the Neely Mansion used the small building primarily for storage, and over the years it fell into disrepair.

In 2013, the Neely Mansion Association, a volunteer-run historical society, came together to restore the Bathhouse, securing the funding, researching the history, conducting oral interviews, and realizing the vision to repair the structure.

BACKGROUND

The 10’ x 16’ structure was originally constructed in 1930 by Shigeichi Hori, and was used for daily bathing, laundry, and contained the property's only flushing toilet. According to the King County Landmark nomination, it is the only known remaining Japanese Bathhouse in the White River Valley, where the building type was once ubiquitous among Japanese farmers.

After years of changed tenancy and ownership of the main house, the Bathhouse was relocated in the 1980s to an adjacent site where it was used as a shed, and maybe a poultry roost. In 1998, it was stabilized and relocated back to its current site, in approximately the original location according to historic photographs, where the Neely Mansion Association planned to restore it as an interpretive exhibit. Sadly, the unprotected exterior had suffered from years of neglect, and the loss of original interior building fabric left many questions unanswered.

The Association established a Bathhouse Committee in late 2013. It began meeting monthly to document existing conditions, research historic records, and contract for documentary photographs. It recorded oral histories with Dr. Frank Hori and Mary Hori Nakamura -- two siblings who had once lived with their parents on the property and used the original Bathhouse -- and called on experts with personal experience with this special building type. Through this process, the Committee carefully considered the best methods to recreate missing fabric and reflect the building’s historic character for interpretation. The Association brought in historic preservation architects, BOLA Architecture + Planning, to create drawings and a digital model to awaken 80-year old memories, which helped confirm spatial configurations. It hired a local general contractor, Big Fish Construction, to implement the restoration plan.

RESTORATION

On the exterior, the unpainted wood siding has an unusual lapping pattern – long shiplap planks have the bottom lip lapped onto the face of the board below, creating a shingled effect, rather than a smooth, flat finish. On the interior, the studs were visible, exposing the backside of the exterior siding. Since the poor condition of the siding did not allow for preservation of the structure for longevity or for any kind of archival use, the existing siding was removed and salvaged. New rough-sawn straight lap sheathing, the size of the original siding, was installed, layered with new building paper, and the original, repaired siding was reinstalled. The wood was stabilized and protected on all sides with an application of clear penetrating oil to preserve the original untreated appearance.

While every effort was made to salvage and reinstall the original siding in the original locations, the material was brittle and fragile, necessitating replacement in some places. Salvaged or new material, reasonably matching the species, profile, surface textures, and weathered color of the existing siding, was used to patch in missing boards. The newer boards were treated with a baking soda and vinegar mixture to speed up the darker, weathered appearance.

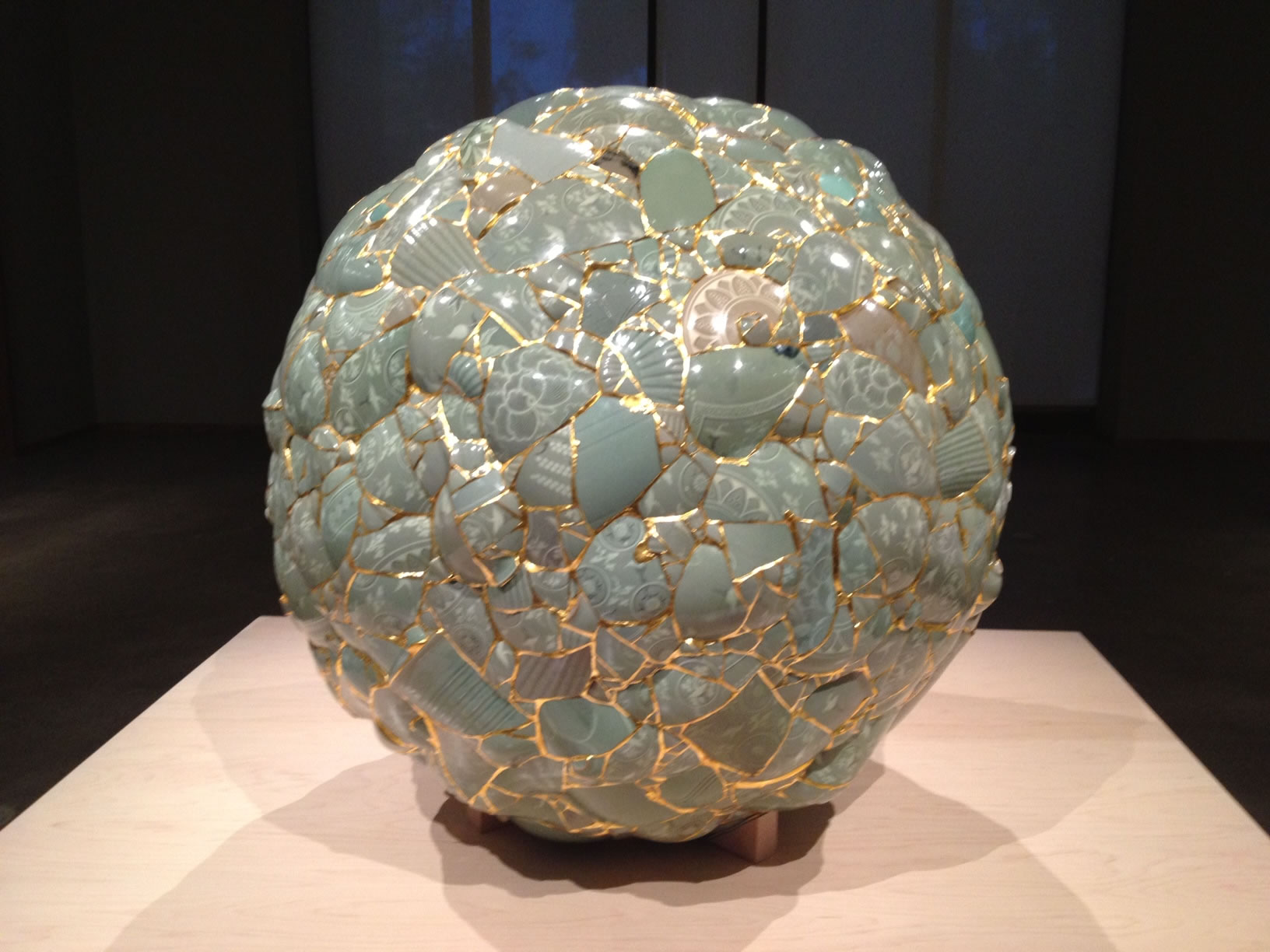

As a subtle indication of the new siding, and with a nod to Japanese culture, an architectural interpretation of an ancient Japanese pottery repair technique called kintsukuroi was employed. This repair traditionally involves reassembling the broken pieces, using metallic materials to highlight the repairs. The process accepts and honors the intrinsic value of the original piece; increases the value by the addition of precious metal; is understood to become more beautiful for being broken; and gives new service life to the artifact. In the architectural interpretation here, where repairs were made to the original siding, the darkened metal infill material was allowed to show through, to subtly identify the new material used to repair the Bathhouse.

According to historic records and oral histories, the building had a smooth gapped wood plank floor laid over wood framing, which allowed bathing water to drain through. There was no foundation, but perhaps brick or masonry block which provided a firebox beneath the tub. To protect it and interior artifacts from moisture and pests, the building was placed on a concrete slab and continuous foundation, with a small recess for the interpretive tub-heating fire box at the east end. Gapped, smooth floor boards were installed on sleepers above the slab to recreate the historic appearance.

The interior had retained a variety of original and new framing members and other elements added when the building was used as a storage shed, including original wall sheathing, doubled studs at rotted bottoms, and diagonal bracing. New framing was needed to complete the proposed structural stabilization, while unneeded non-original bracing was removed. To achieve a less jarring visual appearance, and a more accurate representation of the original unfinished interior, the original wood was lightly sanded to expose lighter surfaces, adjacent to new sheathing and floor planks, and to brighten the space as it would have appeared when originally constructed.

The reconstructed oval soaking tub was the result of extensive research. It was determined to have been originally fabricated with a metal bottom (with a fire directly below, fueled from the exterior), and tight wood slats on the sides, like a barrel. On the interior, a wooden "raft" floated on the water to be stepped onto and submerged to prevent touching the hot metal with bare skin during a soak.

Appropriate salvaged items were secured from various public and private sources, including the laundry area window, the front door, and period toilet and washing machine. The “new” window and doors were consistent with oral histories and the 1939 tax photo.

At an earlier time, a non-original window had been installed in the bath area of the building. As part of the interpretive plan, this opening was strategically converted to a "peeking window," allowing visitors the opportunity to view the bath area without entering the building. A plexiglass panel was installed and two "shutters" of matching wood siding cover the opening when closed.

The completed project will more fully interpret the role of Japanese American farming in the valley. Planning for the restoration and construction was significantly funded by a generous grant from King County’s 4Culture Special Projects program. An opening dedication ceremony will be held at the site on June 25, 2016.

IMAGES

Figure 1: 1939 Tax Assessor’s Photo, with the Neely Mansion prior to restoration, and bathhouse on the right.

Figure 2: As-found condition in 2015.

Figure 3: As-found condition in 2015.

Figure 4: Exterior siding repair.

Figure 5A: Example of artistic Japanese ceramic repair technique.

Figure 5B: Example of artistic Japanese ceramic repair technique.

Figure 6: Partially sheathed furoba being lifted onto a new foundation.

Figure 7: Interior before.

Figure 8: Interior after with "new" laundry tub.

Figure 9: Newly constructed tub, inspired by the Hori's oral accounts.

Figure 10: South façade of the restored furoba, completed in February 2016, with open "peeking" window.

________________________________________________________

BOLA Architecture + Planning is a small, entrepreneurial firm with a professional staff of five who focus solely on historic buildings and sites. They work extensively with the standards and guidelines for historic rehabilitation, and are experienced melding older technologies and construction types with contemporary codes and systems, and have worked on over 200 local or National Register properties. In addition to architectural planning, design, and construction projects, BOLA also specializes in design review and agency negotiation assistance; historic resources research, surveys and landmark designations; building documentation and condition surveys; federal and local tax credit certification applications; and evaluations and impact assessments for SEPA/NEPA and Section 106 Review.

The future and the past are not incompatible. With this philosophy, our design and planning concepts address specific project requirements and goals. We maintain passionate interests in history, preservation, and the continued use of buildings and sites. Our designs preserve the unique qualities of building craftsmanship, materials and forms, and incorporate these into additions, and restorations and rehabilitations to revitalize the existing structures and sites.