- Home

- 2021 Cummings

2021 Cummings Award

Thomas C Hubka

How the Working-Class Home became Modern, 1900-1940

University of Minnesota Press, 2020

In a field of extraordinary new publications covering a wide range of buildings and landscapes from California to Germany, this year’s Abbott Lowell Cummings Award winner forces us to rethink something we thought we understood: common American housing in the first half of the twentieth century. Thomas C. Hubka’s, How the Working-Class Home became Modern, 1900-1940, is an important and beautiful book, the culmination of decades of Hubka’s patient and rigorous fieldwork, and a discerning analysis of buildings, documents, and previous scholarship.

Hubka’s book delineates the critically important, yet often overlooked, steady and dramatic improvements in the basic amenities of working-class homes, a process long missed by scholars who examined housing by reading prescriptive and marketing literature and paying primary attention to new houses designed for wealthier Americans. In 1900, a surprising number of the residences of those Hubka calls the “middle majority” still lacked amenities such as three-fixture bathrooms, electricity, and bedroom privacy. But by 1940, a remarkably short period of transformation including the Great Depression, huge gains had been made, pushing this middle majority towards a common material life of middle-class comfort. The working class often obtained this convenience and status through the remodeling of existing housing and in multiple family dwellings.

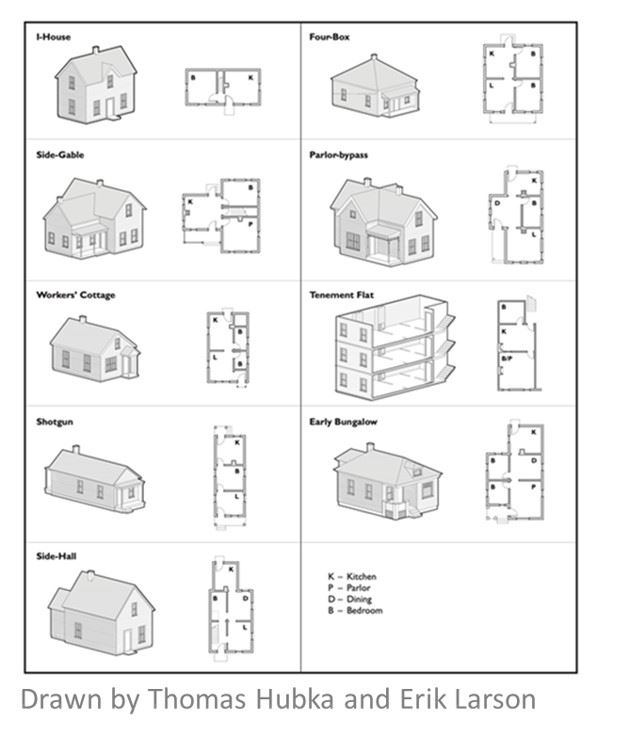

Hubka documents these rapid and far-reaching changes through systematic fieldwork in over twenty towns and regions. Building on the national sampling survey methodology of his previous book, Houses without Names, and incorporating the scholarship of others such as Thomas Carter, Elizabeth Cromley, Howard Davis, Henry Glassie, Paul Groth, Marta Gutman, Richard Harris and Kingston Heath, among others. Hubka looked for incremental changes in spatial arrangements and technical amenities. This book is not about architectural style, but the experience of domestic space and how it changed. By concentrating on domestic functions—kitchens, separate dining rooms, bathrooms, electricity, and increased privacy—Hubka shows how the basic modern bungalow plan came to dominate all housing.

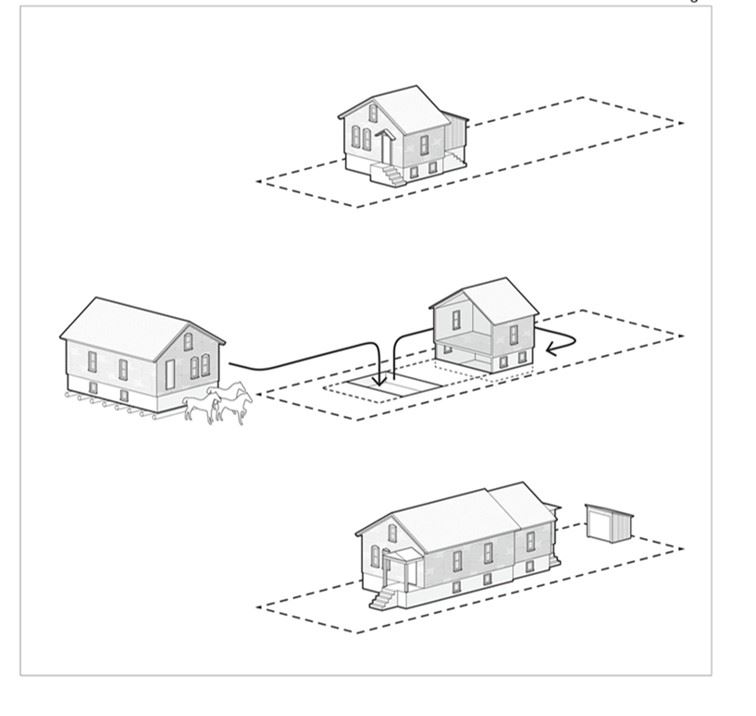

The social world of building that Hubka describes is local and adaptive, a community of people with a range of skill and experience who, through their partial contributions, constructed and reconstructed the majority of common housing. One example he describes in detail is the Mazur house in Milwaukee, begun in 1889 as a wood-frame worker’s cottage with two rooms and a kitchen shed. Twenty-three years later the family split, reoriented, and reattached this house to another cottage, resulting in a modern, seven-room bungalow with many features of a “middle-class lifestyle.” With a gentle yet persuasive critique, Hubka respectfully takes on ideas firmly planted in the history of American housing, such as the “shrinking“ of the average house after the Victorian period, or the idea that progress brought “more work for mother” –not so for Americans, like the Mazur family, documented in this book.

This book is a joy to read. The University of Minnesota Press’s high production quality does justice to Hubka’s lucid prose, logical organization, and the plentiful telling diagrams and photographs that demonstrate his conclusions with striking clarity. Floor plans, timelines visualizing the growing presence of amenities, and clever schematics illustrate why these most common, important houses have been “hidden in plain sight.”