by David S. Rotenstein

***Editor's Note: To view captions, hover your cursor over photos.

Introduction

This is a story that begins in the Prohibition era. It is about a long-overlooked vernacular building found in Pennsylvania: the beer distributorship.

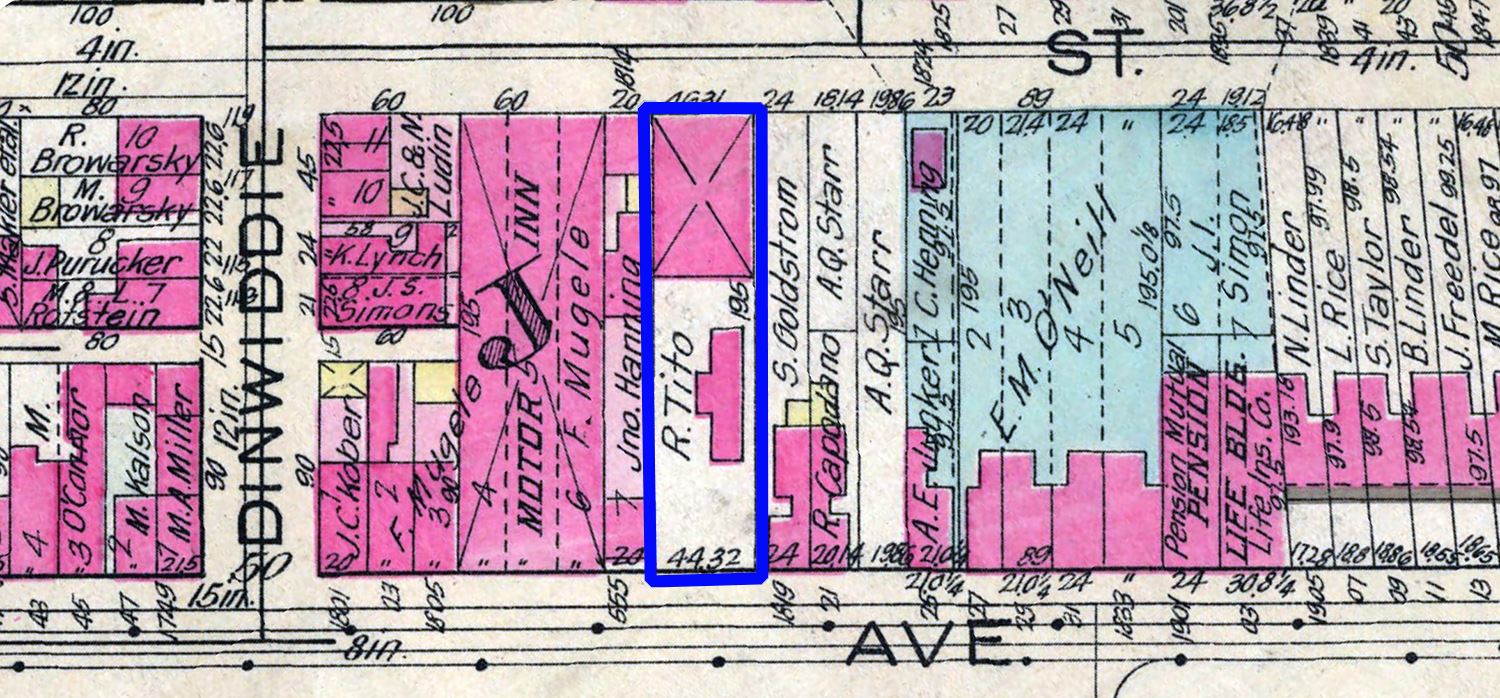

Last summer I led a walking tour of sites associated with organized crime history along Fifth Avenue in Pittsburgh’s Uptown neighborhood. One of the tour stops is a Victorian home once owned by a bootlegger and numbers banker named Joe Tito. After Prohibition ended, Joe and two of his brothers bought a flagging brewery east of Pittsburgh and in 1935 they introduced Rolling Rock beer to the world. During the tour, one of the participants — a man who had grown up in the neighborhood — asked me if I knew about the beer distributorship in back of the house. I replied that I had not.

The day after the June 2021 tour, I returned to Uptown and visited the beer distributorship building. It looked like an ordinary garage and, except for a metal sign bracket attached to its façade and heavy metal wheel guards at the entrance, there were no outward signs of its earlier use. I had originally missed the building while designing the walking tour of the Fifth Avenue corridor because the parcel on which it was located had been sold by the Tito family in the 1960s and it had a Colwell Street address, not a Fifth Avenue one.

My organized crime history research isn’t necessarily a historic preservation project. I designed the tours as a tool to engage the public about the city’s significant numbers gambling history and I wanted to use the built environment to help tell the stories. That June walking tour led to me research and write a local landmark nomination for the former Tito house and the beer distributorship. This essay explores some of what I learned about the Tito beer distributorship and its place as a material culture expression of Pennsylvania’s post-Prohibition liquor laws.

My organized crime history research isn’t necessarily a historic preservation project. I designed the tours as a tool to engage the public about the city’s significant numbers gambling history and I wanted to use the built environment to help tell the stories. That June walking tour led to me research and write a local landmark nomination for the former Tito house and the beer distributorship. This essay explores some of what I learned about the Tito beer distributorship and its place as a material culture expression of Pennsylvania’s post-Prohibition liquor laws.

Prohibition and its Entrepreneurs

In 1919, the United States Congress passed the eighteenth amendment to the Constitution, which made illegal the manufacture, transportation, and sale of intoxicating liquors. The amendment went to the states for ratification and Congress then passed the “Volstead Act” which implemented the amendment. On January 17, 1920, Prohibition became the law of the land and with it came new economies, cultural patterns, and material culture that have become embedded in American popular culture. Bootleggers, once known as local outlaws became legendary folk heroes who laid the foundation for the national organized crime network that came to be known as La Cosa Nostra or (inaccurately), the Mafia.[1]

In Pennsylvania, Prohibition’s cultural influences extended to vernacular architecture. There and in other parts of the country, bootleggers adapted the newly introduced automobile garage as a space for manufacturing and storing beer and liquor. The garage itself is an adapted architectural form with its origins in stables, carriage houses, and other buildings designed to house draft animals and transportation devices. After Prohibition’s repeal in 1933, Pennsylvania passed new laws to regulate the manufacture, transportation, and sale of beer, wine, and liquor. The state’s new laws also created a distinctive type of business: the beer distributor. The new type of business adapted the automobile garage to the bulk sale of beer.

After much wrangling between Pennsylvania’s staunch Prohibitionist governor, Gifford Pinchot, and legislators eager for the state’s entrepreneurs to begin manufacturing and selling liquors, beer, and wine, Pennsylvania passed a beer act in May of 1933. The new law passed one month after the governor vetoed an earlier bill that critics claimed would have fostered corruption.

Pennsylvania’s beer act went into effect in June of 1933. It prohibited bars and limited retail beer sales to eating establishments. Retail establishments could only sell individual beers in quantities up to the equivalent of two six-packs. Beer distributors were prohibited from allowing consumption on their premises and could only sell originally packaged cases and kegs.[2] Beer could legally be sold and consumed, but the new law’s restrictive requirements for licensing and compliance made it very difficult for consumers, retailers, and wholesalers. Nearly a century later, the licensing and regulatory structure continue to make buying beer and liquor in Pennsylvania difficult.

The Garage: Adaptability and Ubiquity

Places to store and service automobiles appeared soon after cars began appearing in American streets in the years bracketing the turn of the twentieth century. “Many of the earliest garages were either makeshift structures, modified from a barn, shed, or mechanic’s workshop,” wrote Jonathan Sager in a 2002 University of Georgia historic preservation master’s thesis.[3]

Within a couple of decades, the earliest garages had evolved into liminal spaces where domesticity, commerce, creativity, and transportation overlapped. These changes flourished starting in the 1920s as automotive technology improved and dedicated automobile service and filling stations began to spread across the landscape. “By the late 1920s, the garage workbench had often been transformed into father's home repair and hobby bench … homeowners began to think of the garage as a safe place to store garden tools, baby carriages, and other household overflow.”[4]

The twentieth century garage, wrote Olivia Erlanger and Luis Ortega Govela, was “a vehicle to deconstruct the entrepreneur and the radical individual.”[5] Their slim volume, simply titled Garage, is a survey of the structure’s multiple meanings and uses that transcend storing cars. Garages birthed businesses and bands, from Hewlett-Packard and Apple to rock musicians whose family garages doubled as rehearsal studios. Pittsburgh engineer Frank Conrad established commercial radio’s first broadcast studio in his suburban garage.[6]

From Batteries to Bootlegging

The garage almost became a natural space for bootleggers. After Prohibition went into effect, liquor and beer entrepreneurs found additional uses for commercial and private garages: places to manufacture and store illegal alcohol. One history of Prohibition in Nebraska noted, “As portrayed in the movies, garages played an important part in the transporting of whiskey.”[7] Rented became key sites for bootlegging activities.[8]

The Titos’ beer distributorship offers us a window into the garage’s incorporation into bootlegging and later legal beer sales. The Tito boys, as they were known around Pittsburgh, were well-positioned to enter the legal beer business after more than a decade transporting and selling bootleg beer. They were a well-rounded family of entertainment and hospitality entrepreneurs when they went into the legal beer business.

In late 1932, Joe (1890-1949), Anthony (1901-1956), and Robert (1905-1949) Tito bought the Pittsburgh Brewing Company’s assets in Latrobe, a Westmoreland County, Pennsylvania, city about 45 miles east of Pittsburgh. They received a brewery license in 1934 and the Latrobe Brewing Company soon began producing and selling beer. Frank Tito (1892-1942) got a Pennsylvania Liquor Control Board distributor’s license.

In late 1932, Joe (1890-1949), Anthony (1901-1956), and Robert (1905-1949) Tito bought the Pittsburgh Brewing Company’s assets in Latrobe, a Westmoreland County, Pennsylvania, city about 45 miles east of Pittsburgh. They received a brewery license in 1934 and the Latrobe Brewing Company soon began producing and selling beer. Frank Tito (1892-1942) got a Pennsylvania Liquor Control Board distributor’s license.

Frank set up the family’s beer distributorship in a brick garage the family built in 1922. Located behind the home the family bought that year, the garage became part of the Titos’ legal “hauling” business and their off-the-books bootlegging. Joe stored a fleet of trucks there — vehicles that found themselves in newspaper reports and court proceedings. The building’s construction coincides with the first reported arrests of Titos for bootlegging.[9]

The Tito beer distributorship outlived Frank, who died inside of a heart attack in 1942. His widow Gretchen secured the license and continued running the business. By the late 1940s, beer was being sold out of the building by a firm using the name “Rock Beer Distributing Company.” Rolling Rock beer was its featured brand, according to newspaper advertisements. In the early 1960s, advertisements for the business show that it moved from its longtime address at 1818 Colwell Street to Pittsburgh’s Northside. The move coincided with Gretchen’s sale of the property out of the family.

The Tito beer distributorship outlived Frank, who died inside of a heart attack in 1942. His widow Gretchen secured the license and continued running the business. By the late 1940s, beer was being sold out of the building by a firm using the name “Rock Beer Distributing Company.” Rolling Rock beer was its featured brand, according to newspaper advertisements. In the early 1960s, advertisements for the business show that it moved from its longtime address at 1818 Colwell Street to Pittsburgh’s Northside. The move coincided with Gretchen’s sale of the property out of the family.

The Bigger Picture

The Bigger Picture

The Tito beer distributorship appears to have been one of many similar automobile-related buildings that were adapted as beer distributorships after 1933. Others appear to have been purposely built drawing from the architectural vocabulary found in earlier garages: overhead doors and masonry buildings with little fenestration and ornamentation.

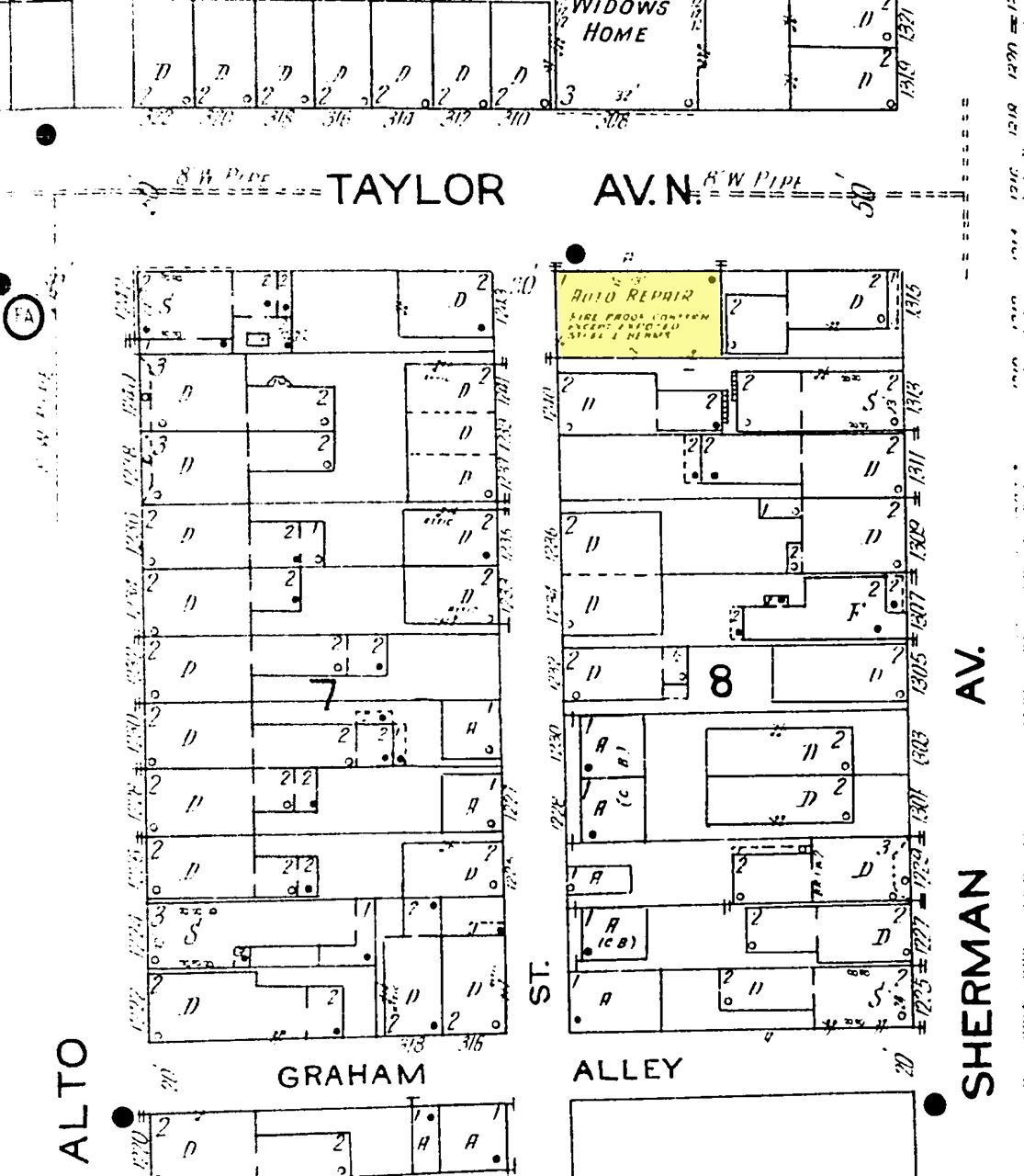

Caruso Beer Distributor in Pittsburgh’s Northside is an excellent example of a building that housed an automobile repair business from the 1920s to the 1960s. AngeloT. (A.T.) Lascher went into the automobile repair business in the mid-1920s after working as an engineer and motion picture entrepreneur. Lascher specialized in automobile electronics, selling and installing batteries and spark plugs, according to advertisements published in Pittsburgh newspapers. Lascher died in 1966. Sam Caruso, who had owned a beer distributorship several blocks away, bought the property and converted it into a beer distributor.

Despite nearly a century of beer distributorships in Pennsylvania, only four are documented in Pennsylvania State Historic Preservation Office inventories and none have been determined eligible for listing nor listed in the National Register of Historic Places.[10] The Pennsylvania beer distributorship building is a unique vernacular architectural form that is ripe for deeper study. First-generation beer distributors like the Tito building may be an endangered historic resource because few historic preservation surveys get beyond superficial architectural descriptions and they are easily written off as not historically significant or lacking architectural integrity.

Notes

Notes

[1] “House Passes Beer Bill That Faces Pinchot Veto,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, April 18, 1933; “New Beer Bill Rushed After Pinchot Veto,” Philadelphia Inquirer, April 21, 1933; “Governor Signs Beer Regulation and Repeal Bills,” Philadelphia Inquirer, May 4, 1933.

[2] Suzanne Laucks, “Brewing up Changes: Pennsylvania Should Modernize Its Tax Laws and Policies to Encourage the Growth of Its Craft Brewing Industry Note,” Pittsburgh Tax Review 14, no. 1 (2017 2016): 119–50; Emma Snyder, “Privatization in Pennsylvania: How Reforming the Pennsylvania Liquor Code Would Benefit the Commonwealth and It Citizens Comment,” Penn State Law Review 119, no. 1 (2015 2014): 27

[3] Jonathan E. Sager, “The Garage: Its History and Preservation” (Thesis, University of Georgia, 2002), 7.

[4] Leslie G. Goat, “Housing the Horseless Carriage: America’s Early Private Garages,” Perspectives in Vernacular Architecture 3 (1989): 68–69, https://doi.org/10.2307/3514294.

[5] Olivia Erlanger and Luis Ortega Govela, Garage (Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 2018), 4.

[6] Erlanger and Ortega Govela, Garage; “A House for the Automobile - Old House Journal Magazine,” Old House Journal Magazine - Renovation DIY and Old-House Restoration, Traditional Styles, Period Kitchens, Historical Decorating, Period Gardens, from Colonial and Victorian through Arts & Crafts and Mid-Century Modern: All from Old-House Journal Magazine and Special-Interest Titles Old-House Interiors, New Old House, and Early Homes. (blog), January 6, 2010, https://www.oldhouseonline.com/gardens-and-exteriors/a-house-for-the-automobile/; Nikil Saval, “How the Garage Became America’s Favorite Room,” The New Yorker, January 14, 2019, http://www.newyorker.com/culture/dept-of-design/how-the-garage-became-americas-favorite-room; “Conrad’s Garage,” All Things Considered (NPR, November 30, 2005), https://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=3059095.

[7] “Historical Details,” Niobrara County Library (blog), accessed September 21, 2021, https://www.niobraracountylibrary.org/historicals/

[8] Allan S. Everest, “Officer Confronts Bootlegger,” in Rum Across the Border, The Prohibition Era in Northern New York (Syracuse University Press, 1978), 109–10, https://doi.org/10.23

[9] “128 Stills and Parts Are Seized in Penn Avenue Raids,” Pittsburgh Daily Post, December 14, 1922.

[10] PA-SHARE database, Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, https://share.phmc.pa.gov/pashare/landing, accessed August 22, 2021.